|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

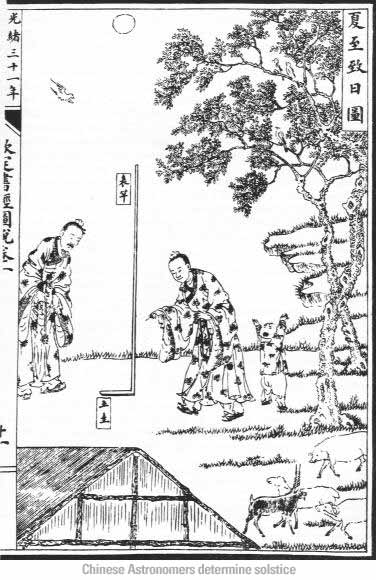

As with other early agricultural societies, the ability to predict changes in the seasons, to know when to plant one’s crops, was necessary for the survival and growth of the Chinese population. The earliest known astronomical tools were designed for exactly this purpose; four thousand years ago, a simple, 8’ bamboo pole planted in the earth allowed court astronomers to observe changes in its shadow over the course of the year. Noting that the shadow was longest when the sun took its lowest path across the sky, they realized they had a tool with which to mark the winter solstice. As the sun climbed higher, the days gradually grew warmer and daylight lengthened. Having consumed their stored food during the cold winter months, the Chinese had ‘eaten the old year’. The New Year began in the warmth of the second new moon, following the winter solstice.

The celebration of the New Year is known as the Spring Festival. As the month of the traditional Chinese calendar is dictated by the lunar cycle, the festival culminates on the full moon, after a two-week period of celebration. According to folklore, fortunes for the year are swayed during this influential period; one is not to sweep for fear of driving out prosperity, nor use a knife lest one introduce discord and strife to the household. In 104 BCE Chinese astronomers had determined the length of the solar year to an accuracy of 365.2502 days. By 480 CE this was further refined to 365.2428 days, only 52 seconds longer than today’s modern value. Astronomers recognized that without a system to balance their lunar year of 354 days (12 lunar cycles of 29.5 days) with their calculations of the solar year, their predictions of seasonal flooding and advantageous harvest dates would grow less and less accurate. To compensate, they introduced an intercalary month every 2 – 3 years. Unlike the extra day of the Gregorian system, this ‘leap month’ duplicates its predecessor. If you are lucky, you could therefore end up with two birthdays within two months! The oldest star charts still in existence are Chinese. Dated 618 – 906 CE and likely drawing on a much earlier source, the Dunhuang star maps divide the sky in the northern hemisphere into 12 sections, based on the stations of Jupiter. Jupiter, the ‘year star’ (sui hsing) takes 12 years to complete its orbit, giving us a 12-year cycle, or the ‘Earthly Branch’ component of the traditional Chinese calendar. The years are named for the 12 different animals whom, according to tradition, responded to Buddha’s call as he departed the terrestrial realm. Each of these years is said to be characterized by the nature of its namesake animal. Together, the 12 years equal one ‘Great Year’ in the calendar.

To calculate the year according to the traditional Chinese calendar, one employs a sexagenary cycle of the 12 Earthly Branches in connection with 10 Celestial Stems. These ten archaic ideograms are associated with 5 elements: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water. Each element is further identified as either Yin (receptive, creative, female) or Yang (active, productive, male), bringing the total number of Heavenly Stems to 10.

As each of the earthly branches can only exist in a yin or yang year (Dragon Year is always yang, Snake is always yin…) a 60-year cycle is created of 5 Great Years. The current cycle began in 1984 with the year of the Wood Rat, heavenly branch jia, earthly stem zi.

When this system was first described, attaining 60 years of age was a remarkable achievement. These 5 Great Years, each characterized by the element associated with its inception, are therefore also used to describe the course of individual existence. The first Great Year of life, from birth to age 12, is an era of growth and physicality, ruled by the element of wood. Fire characterizes the next stage of development, energy and transformation being essential to the emerging adult. From twenty-five to thirty-six, one concerns oneself with the material stability symbolized by earth. As confidence and power solidify in later adulthood, one attains the dominance and mastery of the element metal. Finally, at the ripe old age of 49, one is ready to settle into the quiet reflection symbolized by water. Although the Chinese calendar was officially replaced with the Gregorian system in 1911, it is still widely consulted for the traditional wisdom it contains. Its usage allows us a brief glimpse into the minds of the world’s most ancient, documented astronomers. On January 29th, we’ll enter the year of the Fire Dog; bing-xu. Those early sky-watchers would tell us that the industrious, loyal, creative and judicious will be well rewarded in the year to come.

"Gung Hay Fat Choy" is the traditional New Year's greeting in Cantonese, a dialect of Chinese, and literally means "Congratulations and Best Wishes for a Prosperous Year!" In Mandarin, the official Chinese dialect, the literal translation of "Happy New Year!" is pronounced "Xin Nian Kuai Le!" Claire Rothfels Sources: |

Feb 2006

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here’s a riddle for you. Of the seven brightest objects in the sky, which one have most amateur astronomers never seen? The answer is Mercury. At its brightest, it rivals Sirius and outshines Saturn, but very few people have ever seen it. The problem is that it never strays far from the Sun, and, because of the geometry of the ecliptic, it’s only well placed a couple of times in the year. This is once in the evening sky in the spring and again in the morning sky in the fall, times when the ecliptic makes a steep angle relative to the horizon. February is one of those rare windows in which Mercury is well placed for observers in the Northern Hemisphere in the evening just after sunset. It will be best placed at the time of Eastern elongation on February 24, when it is farthest from the Sun, but it can usually be spotted a week or so before or after that date.

For viewers at about 45° north latitude, Mercury will be almost directly above the point where the Sun sets. You won’t be able to see it at first because of the glare from the sunset. But if you sweep the area with binoculars you will soon pick it up as a tiny speck of light in the twilight glow. (Do not look at the Sun through binoculars directly as it will cause permanent eye damage - sweep for Mercury only after you are sure the Sun is below the horizon). As the sky gets darker, Mercury will be easier to see, but will also be sinking lower and lower in the sky. Soon it will be visible to your naked eye, now that you know where to look. The view of Mercury through a telescope may be disappointing. You should be able to see its tiny disk, smaller than Mars is currently, and make out its phase. Like Venus, Mercury shows phases because it is closer to the Sun than the Earth. However, because it is so close to the horizon, its image will usually be bubbling from the effects of our atmosphere, and smeared into a spectrum from atmospheric refraction. If you note carefully the spot where Mercury appears relative to terrestrial landmarks, you should be able to pick it up earlier the next night, which will give you an opportunity to observe it higher in the sky. And you can congratulate yourself on seeing something that relatively few other people have ever seen! Geoff Gaherty |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gaze at the night sky through the Orion Binocular Viewer and you’ll be hooked! Familiar objects take on a 3D-like appearance. The effect is more distinct on the Moon and planets but even deep sky objects will benefit from finer detail with better contrast. For the ultimate visual experience, nothing beats two-eye observing. What is a binocular viewer? A binocular viewer, sometimes called a binoviewer, looks like a small pair of binoculars except that it has no lenses and has only a single hole in front. You insert the binoviewer into the eyepiece holder of your telescope. A system of prisms inside the binoviewer splits the light into two parallel paths and feeds each to an eyepiece and then to your two eyes. This has long been a standard accessory for microscopes, but only recently has begun to become popular for use with telescopes. Observing with two eyes is more comfortable than observing with just one. As an added advantage, the brain can also compensate for optical deficiencies in our eyes when both are used.

In a binoviewer, the light is divided in two and several prisms are introduced into the optical path, the images are dimmer than those with a single eyepiece, though not as dim as one might expect, thanks to the way the brain integrates the images. The main optical problem is that any binoviewer introduces a sizable distance into the optical path, requiring four inches (in the case of the Orion model) of inward travel to reach focus. If you own a Schmidt-Cassegrain or Maksutov-Cassegrain which focuses by moving the primary mirror (as most do) you should have enough focus travel to reach focus with a binoviewer. With a typical refractor or reflector you may need a short 2X Barlow to gain extra back focus - more about this later. Until recently, Binoviewers have been expensive — between $700 and $1600 — and then required the user to purchase eyepieces in pairs. You still have to purchase pairs of eyepieces, but the cost of a binoviewer has dropped down to a much more reasonable $199.95 with the Orion Binocular Viewer. The Orion binoviewer, unlike some more expensive models, is equipped with individual helical focusers for both eyepieces, important if your eyes are not exactly alike. Each eyepiece is held in place by three knurled nylon screws. If this seems like overkill, it’s a really important feature as it ensures accurate centering of the eyepieces; otherwise you can have trouble merging the two images. The binoviewer comes in a nice little hard case with room for a pair of eyepieces and a Barlow lens. I tested the Orion binoviewer on three typical telescopes: a Meade ETX90 Maksutov-Cassegrain, an Orion 100mm ED refractor, and an Orion SkyQuest XT6 IntelliScope reflector. I used a pair of Orion Sirius 25mm Plössl eyepieces. Because of the Maksutov’s moving mirror focusing, the binoviewer reached focus without any problems. With the two other telescopes, there was insufficient focus travel to reach focus with the binoviewer by itself. To help reach focus on the reflector and refractor I used a Barlow lens. A Barlow lens, as well as increasing the apparent focal length of a telescope, also moves the focal point farther away from the focuser, which is exactly what we want to do to use a binoviewer. Because the projection distance (the distance from the Barlow lens to the focal point of the eyepiece) is greater with a binoviewer than if the eyepiece were directly inserted into the Barlow, the magnification factor of the Barlow is also increased. Using a 2x Orion Shorty or Shorty Plus Barlow between the binoviewer and the telescope yields about a 3.1x magnification factor. Thus my 25mm eyepieces functioned in the binoviewer as if they were 8mm eyepieces! This is fine for lunar and planetary observing, which is the binoviewer’s strong suit. For deep sky observing you will want to use your wide field eyepieces. There are a couple of ways to get lower magnifications. The Orion Shorty Barlow (not the Shorty Plus) has the actual lens mounted in a black metal cell: This cell can be unscrewed from the body of the Barlow, and exactly fits the filter threads in the inlet of the binoviewer. Doing this reduces the magnification factor to 2.8x and makes a nice compact unit that fits easily into the carrying case. Although you have to buy two of every eyepiece, it’s not all that bad. Because you’re working at relatively long effective focal ratios, you don’t need expensive eyepieces. I found the Orion Sirius eyepieces did the job very well; Orion Ultrascopics also work very well in binoviewers. For lunar and planetary viewing with the telescopes considered here, a focal length somewhat shorter than the 25mm I used would be better. I’ve had success with 16mm Plössls, so something in the range of 17mm to 15mm might work well. Even though the view through a binoviewer is not truly three-dimensional (since the view going to each eye is exactly the same, hence no stereoscopic effect), the 3D-like effect of the images would make you think otherwise. I find the “bino” views of the Moon especially exciting. The terrain takes on a new life, and you get a real feeling of hovering over the lunar surface in a space vehicle. Jupiter reveals to me more and finer detail in its cloud tops with a binoviewer than I ever experienced before. Saturn with its rings and many moons is striking. Among deep sky objects, I particularly enjoy looking at globular clusters with a binoviewer. Again, they take on an eerie three-dimensional quality. The Orion Nebula also looks almost like a three-dimensional object with many ghostly wisps and tendrils. I’ve been hooked on binoviewers for a number of years, and now find it very hard to go back to “Cyclops viewing,” as we binoviewer aficionados call it. If you’ve become bored with visual observing, now is the time to give a binoviewer a try! Geoff Gaherty |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the night of January 31st, stargazers will be able to use Saturn to help them locate the Beehive Cluster (M44). This is because at 11 p.m. Saturn will be less than one degree south of the Beehive. Both objects are normally visible to the unaided eye. For the best viewing experience use a pair of binoculars or a telescope under low power so that both the Beehive and Saturn are in the same field of view.

At 3 a.m. on the night of February 6th, the First Quarter Moon will be a mere 0.1 degrees from the Pleiades Cluster (M45). The Pleiades contains about 500 member stars, but most will be washed out by the brightness of the Moon. Use a pair of binoculars to see the brighter members of the Pleiades and the cratered face of the Moon in the same field of view. Pedro Braganca |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Auriga is most notable for its three bright open clusters and for sporting one of the ten brightest stars in the night sky, Capella. In ascending order of interest are Auriga's three Messier-designated open clusters: M36, M38 and M37. All are clearly visible to the naked eye from a dark site and, in binoculars, appear as bright fuzzy patches; naturally, a telescope brings out the most detail. M36 will show around 50 stars in an 8" scope while M38 shows twice as many stars, some in apparent chain-like arrangements. But the most notable of the trio is M37. In a 12" scope, roughly 150 starts are visible in this neatly arranged cluster, some tinged red. NGC 1931 is a bright emission nebula surrounding a very small open cluster. With high magnification in an 8" telescope, the nebula is quite apparent. Sean O'Dwyer, Starry Night® Times Editor

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This image of the Long Nights Moon was shot on Highway 287 south of Longmont, Colorado, through Edward Kelley’s Nikon Coolpix 5700 on December 15th, 2005 at 7:19 a.m. local time. Long Nights Moon is the full Moon closest to the winter solstice – the longest night of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. PHOTO OF THE MONTH COMPETITION: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter. Featured submissions (best of month) will receive a prize of $25 USD. Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.