|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. We hope you enjoy this month’s newsletter. It’s filled with engaging and in-depth articles on the lore, history and science of eclipses—including a free interactive SkyGuide tour illustrating the upcoming March 29, 2006 total solar eclipse. In our feature article—"And the Sun Perished out of Heaven"—Claire Rothfels takes us on a journey backward in time to explore the influence of eclipses throughout the ages. Geoff Gaherty is our knowledgeable guide to the science of eclipses, providing observing tips for those lucky enough to be in the path of totality. While Jim Low reminds us that sometimes watching an eclipse is only a small part of the reason one travels the world to see them. We packed a lot more in this month’s newsletter… happy reading. Pedro Braganca

Eclipse Lore and Legend Imagine living in a world without advanced astronomical reckoning. Imagine your world plunging into sudden darkness, the animals growing eerily silent. Imagine witnessing the sun, your source of warmth and life, being consumed by a swiftly encroaching shadow, leaving only a blinding hole in its wake. The solar eclipse has always been seen as a powerful omen, variously ill and auspicious. This awesome sight has influenced wars, ended lives, made regular appearances in literature and, even with a modern comprehension of the forces at play, still holds a powerful hold over our collective imaginations. It is no wonder that the solar eclipse, which occurs only once in most life times, is the stuff of legend. The history of the eclipse is divided between those who were able to predict its occurrence, and those who were taken by surprise. Though the tale may be apocryphal, the oft-repeated example of Columbus’ manipulation of native Jamaicans is illustrative. The fellow apparently became stranded and ran out of supplies during his fourth trip to the new land, and he needed help. Rather than replenishing his resources, the inhospitable locals expressed their displeasure at his appearance by refusing sustenance and aid. It was only Columbus’ ability to predict a fortunate lunar eclipse that saved him; announcing the great displeasure with which heavenly forces viewed the natives’ reticence, Columbus claimed that the moon would be struck from the sky should the natives fail to assist him. How would the course of history have been affected, had the eclipse not come to pass? Download Starry Night File (SNF): Columbus Lunar Eclipse (1504 CE)

When eclipses occur unexpectedly, they have profound influence on world events. Take this tale of two wars; in 413 BCE a surprise eclipse convinced Athenian strategists of the Peloponnesian war that a planned retreat was ill advised. Delaying the move led to the easy slaughter of their troops; an early and unnecessary defeat at the hands of the Syracusans. Contrarily, in 585 BCE both the Lydians and the Medes saw the eclipse as evidence of heavenly displeasure with their years of war. In this instance, the magnificent sight inspired an early armistice and saved many lives. Download Starry Night File (SNF): Peloponnesian War (413 BCE) This duality in our perception of the eclipse is apparent in world mythology, as well as in our history books. In many places, the disappearance of the sun is an alarming occurrence, attributed to mythical beasts (variously dragons, dogs, birds and demons) that come to consume our life-source. There is a widespread fear that, without intervention, the skies would be permanently darkened and life ever altered. It is only through scaring the Mongolian Sun Eater away with firecrackers, drumming and general cacophony that balance can be restored. While this perception of eclipse as an ill omen is pervasive, there are also many cultures where the event is viewed positively. In Tahiti the eclipse is understood as the lovemaking of the Sun and Moon. Amazonian myth describes a passion so great between these lovers that the earth becomes scorched by the Sun’s heat and drenched from the Moon’s tears; to protect us from their excess, the two will only touch through the shadow of eclipse. This perceived concern for our well-being is reflected again in various Native American mythologies wherein the sun or moon absent themselves from the sky during an eclipse, to check that all is well on earth.

The eclipse as a portent and harbinger of change is a common theme in history, literature and religion. The New Testament Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke all describe a solar eclipse during the crucifixion of Christ, causing his lament ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?’. Indeed, this use of eclipse as metaphor in classical texts has helped scholars to place events in historical context. We can, for example, compare Amos 8:9 of the Old Testament ‘and on that day…I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the Earth in broad daylight’ with Assyrian historical records, to conclude that ‘that day’ occurred on June 15th, 763 BCE. Download Starry Night File (SNF): Crucifixion of Christ (29 CE)

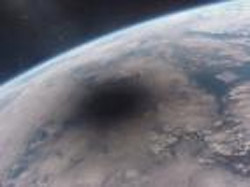

Shadow of the 1999 Total Solar Eclipse as Seen from Space Our advanced astronomical understanding of eclipse phenomena has done nothing to diminish our fascination with the event. The convenience of modern travel now allows millions of spectators to flock to the path of totality for each occurrence. Perhaps there is something here of wonder; the only place in our solar system where the celestial bodies are of the necessary relative size and distance for complete obfuscation just happens to occur where there is life to appreciate the magnificence of the sight! Claire Rothfels

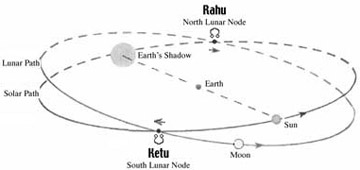

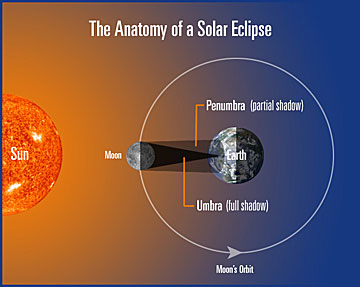

The Solar Eclipse March 29, 2006 In its monthly trip around the Earth, the Moon passes close to the Sun every New Moon. Because the plane of the Moon’s orbit is at an angle to that of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, most of the time the Moon passes either above or below the Sun. When the timing is just right, the Moon actually blocks the light from the Sun, resulting in an eclipse.

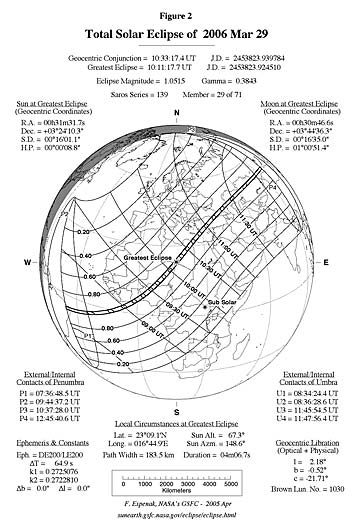

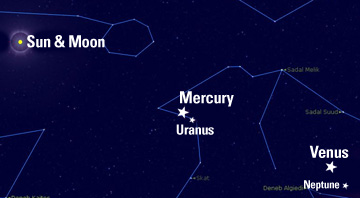

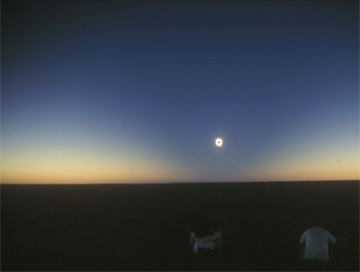

Because the shadow of the Moon is very small on the Earth’s surface, you need to be in exactly the right place at exactly the right time to see a total eclipse. The next time this happens is on March 29. Because the Earth and Moon are both in motion, the tiny dot of shadow, only 184 km in diameter, passes in a long narrow path across the face of the Earth. The Moon’s shadow touches down at sunrise on the extreme eastern tip of Brazil and immediately heads out over the Atlantic Ocean. It makes landfall in Ghana and travels northeastward across the Sahara, passing through Libya and the extreme northwestern corner of Egypt. Crossing the Mediterranean, it moves in between Crete and Cyprus without touching either, and then crosses Turkey, the Black Sea, Georgia, Russia, the Caspian Sea, Kazakhstan, and Russia again before leaving the Earth at sunset in Mongolia. The best places to observe the eclipse along this path are in Libya (where Jim Low and I will be), the Mediterranean (where many cruise ships will be located), and Turkey. These are the places where the Sun will be highest in the sky and the weather prospects the best. At the point of maximum eclipse, in southern Libya, totality will last 4 minutes and 7 seconds. The Moon’s path on the above map has a rather strange shape because the Earth is rotating as the Moon’s shadow sweeps in a straight line across it. To understand what’s really happening, this Starry Night® file <View_from_the_Sun.snf> can show you a view of the eclipse from the point of view of the Sun. Even though the Moon’s shadow will be 184 km in diameter, most observers will be concentrated along a line right in the middle of this path, so as to get the maximum length of eclipse and the most spectacular views. Here they will watch as the Moon slowly moves in front of the Sun’s face until it is almost totally covered, the only light visible being the few scattered beams working their way through valleys at the Moon’s edge, called Baily’s Beads. Then, all light from the Sun’s photosphere will be gone, the sky will become dark enough to see bright stars and planets, and all that will be visible of the Sun will be prominences close to the Moon, and the ghostly glow of the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona. It used to be that these were only visible during eclipses, but nowadays solar telescopes are widely available to view prominences any time. But the corona is still visible only during a total eclipse, and it is to see the corona that people will travel halfway around the world.

Observing a solar eclipse requires relatively simple equipment. Viewing the partial phases requires normal solar filters to cut the Sun’s heat and light to manageable levels. Naked eye observers often use #14 welder’s glass, the greatest density made. This is usually available only from specialized welding supply dealers. Solar filters for telescopes are widely available from most telescope dealers. It’s important to be prepared and have proper solar filters; last minute improvisations can be extremely hazardous and can lead to permanent blindness. With the proper filters, observing a solar eclipse is perfectly safe. At the moment of totality, once the Sun’s photosphere is completely covered by the Moon, it is safe to remove the filters from your eyes or telescope. Only without filters will you see the light of the corona, the whole reason for traveling to an eclipse.

I plan to do something a little different to observe this eclipse. Instead of a normal white light telescope, I plan to use my Coronado HST hydrogen-alpha telescope. This will enable me to watch the activity of the hydrogen in the Sun’s upper atmosphere during the partial phases. At totality, I will switch to my 10x50 binoculars to view the corona and to look for stars and planets near the eclipsed Sun. Wish me luck! Geoff Gaherty

I witnessed my first total solar eclipse in 1963. Nine total solar eclipses later, and I’m still hooked! Over the years, my quest for “totality” has taken me on various eclipse expeditions—what better excuse to see far off and exotic places. There is no need to spend months agonizing over where and when to go. I just let the workings of the universe make the decision for me. Every eclipse I've witnessed has been a profound experience and sometimes the eclipse itself had nothing to do with it. My expeditions have brought the joy of making new friends, renewing old acquaintances and spending time with my family while immersed in a different culture. The eclipse itself is only the climax of a deep personal experience.

My last solar eclipse was the 2002 sunset eclipse in Australia. For the 1988 eclipse I traveled with my two teenage daughters to the Philippines. I had an amazing learning experience traveling with them. In real life, teenagers and their parents just don't make a habit of spending much time together. We were placed into a situation where we actually had to communicate and co-operate—and we did. There were no fights. No tears. No yelling. My daughters were not treated as "cute little kids" on the expedition tour. They were treated as equals and as adults. They were helpful and assisted others and me in various projects. Having them with me made my trip more enjoyable. I started to look at them in a different light. I learned that they had grown up. We developed a new respect for each other. I went off on an adventure with my two little girls. Somewhere, I lost them. But I returned home with two young women. So now you know why I make eclipse expeditions. I will continue making them. But the eclipse will have little to do with my reasons. See you in Libya on March 29! Jim Low

We've been listening—hope you enjoy the improvements. It's a FREE update if you already own Version 5.x If you own Starry Night® version 4.x or lower, save $20 on upgrades to Starry Night Enthusiast, Pro or Pro Plus version 5.x or AstroPhoto Suite. Upon checkout, please be sure to enter coupon code: up5820 Instant $20 savings on upgrades offer expires 3/9/06. NEW IN VERSION 5.8

Note: For our Mac users, the 5.8 update is "Universal Binary" so that Starry Night runs on both Intel- and PowerPC-based Mac computers. Click here for a complete list of enhancements and a quick start guide to access these new features If you already own Starry Night® Enthusiast, Pro or Pro Plus version 5, the update to version 5.8.2 is absolutely FREE! Click here for instructions on how to get your 5.8 update. For your convenience, you can also download the 5.8 update as a standalone updater file. This will allow you to save the update to a CD for example, and then install it later. These updaters contain all the new features and enhancements since the release of version 5.0.0 Enjoy! Pedro Braganca

I don’t know about you, but I’m a total klutz around wires. Even in a brightly lit room, they always get entangled in my feet. At a dark observing site, I become totally lethal to wires and their connectors. The fewer wires I have around, the safer both my equipment and I are. Until now, if you wanted to control your telescope with a laptop computer, you needed to have a wire connection between them. To make matters worse, most telescopes come equipped with an RS232C serial port, while most modern laptops have only USB serial ports, requiring an adapter to complete the connection. Enter the Starry Night® BlueStar Telescope Adapter, a box about the size of a folded cell phone, which connects with a coiled wire to your telescope controller’s RS232C port. Many computers nowadays come already equipped with a Bluetooth transceiver. If yours isn’t, you can buy one to plug into any USB port. The one I used was an IOGEAR GBU311: I found it was very important to follow the installation instructions exactly. First install the Bluetooth driver (if using a separate Bluetooth transceiver like the one above), then the Starry Night® BlueStar driver provided on the CD that comes with it. The BlueStar comes with a preset passkey, “0000” (four zeroes), which you have to enter into your computer. If you need to use the BlueStar on more than one computer (as I had to do for this test), you will have to reset it and reconfigure it when changing computers, but most users will never have to do this. One other technical note is that you must use a telescope-specific cable to connect the BlueStar to your telescope. There are different models of BlueStar, each with their own telescope-specific cable:

At the computer end, most planetarium programs that allow telescope control are supported, though I of course used Starry Night®! (Note: Only Starry Night® Pro, Pro Plus and High School support telescope control). I tested the BlueStar device with two different computers (Dell Inspiron 8100 and Macintosh iBook G4) and two different telescopes, a Meade ETX90 Maksutov-Cassegrain with Autostar GoTo controller, and an Orion SkyQuest XT6 with IntelliScope digital setting circles. Starry Night® uses its own drivers for telescope control in the Mac version and ASCOM drivers in the Windows version, but these function more or less the same. For simplicity’s sake, here I will describe only how the Mac version worked; the Windows version is very similar. With all GoTo scopes you must begin by aligning the telescope using the telescope’s own controller. Once the telescope is aligned and tracking, you set up the connection with Starry Night®. Open the Telescope pane using the Telescope tab at the left side of the screen. Open Setup and click the Configure button. Select BlueStar as the communication port and Meade ETX Autostar as the telescope type, then click OK. Then click the Connect button to connect the telescope to Starry Night®. Under the Control section of the Telescope pane are a number of controls. The “Follow Scope” command will keep the Starry Night® field of view centered on where the telescope is pointing. “Centre indicator” will do the same thing instantly. Onscreen “Nudge” buttons let you center objects in the field of view of the telescope. The screen display will start out pointed at whatever the last alignment star was. To slew to another object, you can use the Find command, and then select “Slew to…” from the menu alongside it, or else simply point to the object on the screen and use the contextual menu that appears to select “Slew to…” That’s all there is to it!

If the alignment starts to drift, you can center the object in the telescope’s field of view using the Nudge buttons, and then use the “Sync to…” command to resynchronize the alignment. The procedure is a bit different with a telescope with digital setting circles such as the Orion IntelliScope. Here there are no driving motors on the telescope’s mount. The user moves the telescope manually until the onscreen indicator is centered on the target. In order to make this work, Starry Night® must first find out where the telescope is pointing. Unlike the procedure with a GoTo telescope, you don’t align the telescope first, except for the very first step. You turn on the IntelliScope controller, point the telescope at the zenith, and press the Enter button on the controller. Then you configure and connect the BlueStar as before, but this time you select “Orion SkyQuest IntelliScope” instead. Now Starry Night® leads you through the telescope alignment procedure, asking you to align on two stars. Once this alignment is complete, Starry Night® displays the position in the sky where the telescope is pointing. As you move the telescope, the onscreen target moves to follow. You move the telescope until the onscreen target is centered on the object you wish to view, and there it will be in the eyepiece. All in all, I found that the BlueStar performed as I expected. As with any GoTo or DSC system, the more care you take with the initial alignment, the more accurate the subsequent pointing will be. I found the system very easy to use with the GoTo telescope. It was a bit more awkward with the IntelliScope because of the need to watch the computer monitor carefully while moving the telescope to the target. It takes a bit of practice to coordinate movements of the tube with the movement of the target on the screen, and you usually have to zoom in when you get close to the target. However, I soon got the hang of it, and was moving around the sky with ease. But best of all, there were no wires for me to trip over! Geoff Gaherty

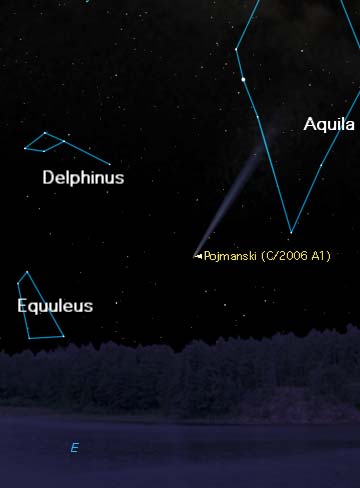

A newly discovered comet is currently visible in binoculars and even with the naked eye from dark sky locations. At the time of this writing, Comet Pojmanski is shinning at magnitude 5.5. The comet can be seen low on the eastern horizon during morning twilight from mid-northern latitudes starting on February 27. It makes the closest approach to Earth on March 5th and then begins to fade as it goes out into the far reaches of the solar system.

Comet Pojmanski at closest approach to Earth on March 5 as seen Binoculars will be your best instrument to view Comet Pojmanski. Look for a fuzzy nucleus with a trailing tail. Pedro Braganca

Lying quietly between Gemini and Leo, Cancer is not the most exciting of constellations. Nonetheless, it holds some modest riches worth checking out. M44, the Beehive Cluster, is a great target for your binoculars or finderscope. More magnification than that and you'll loose the lovely sense of loose structure. Can you spot it naked eye? This month, M44 is easier to locate by eye, thanks to the presence of Saturn, shining a little to the West at Mag 0. Even from your back yard 2,500 lightyears away, you should be able to scoop up M67 in your finderscope or binos. The individual stars of this Mag 6 open cluster will resolve nicely in your telescope's eyepiece. NGC 2775 is a bright spiral galaxy whose core is visible in 8" scopes. Larger scopes will show hints of its spiral-arm structure. Spiral galaxies are the most common kind of galaxy, making up four fifths of all galaxy types, including our own galaxy, the Milky Way. And close by are two more galaxies, NGC 2777, a true gravitational companion of 2775, and NGC 2773 which is four times farther away from us but happens to lie along the same line of sight; you'll need a 10" scope to spot either. At the opposite end of Cancer, Iota Cancri is a nice orange/green double star and well placed to point you just over Cancer's constellation boundary, into Lynx, where the edge-on 10th Mag galaxy NGC 2683 sits. Sean O'Dwyer, Starry Night® Times Editor

|

Mar 2006

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jim Mitchell writes: Without wishing to add to the millions of words written about Stonehenge, I feel a few comments about the lesser-known alignments might be of interest. In modern times, the first person that suggested the stones might be orientated to the Midsummer Sunrise was the antiquarian William Stukeley in 1723. A local, John Smith in 1770, surmised the function of the Heel Stone. However, when Stonehenge was first built, it consisted of a simple ditch and bank with one entrance and the Heel Stone and its possible partner. (It is thought that the original bank and ditch were constructed about 3050BCE and the central stones were constructed, arranged and re-arranged over the period 2500 to 1500 BCE.) The axis of this monument was angled 41 degrees E of N, which agrees with the most northerly rising of the Moon during its 18.61 year Metonic Cycle. A line of postholes near the Heel Stone has been interpreted as the builders marking out successive Moon rises to find this position. Seven hundred years later (c 2100 BCE), the axis was moved 9 degrees to 50 degrees E of N, an alignment reinforced by the first part of the Avenue and the 4 Station Stones. These form a perfect rectangle just inside the bank. The short sides of the rectangle point again to the Midsummer Sunrise. The long sides point surprisingly at the extreme Lunar standstill Moonset. Interestingly, the latitude of Stonehenge is the only place where these alignments form a rectangle, elsewhere they form a parallelogram. The later huge constructions in the centre of the monument comprising the massive Sarsen Stones (brought from the Marlborough Downs, about 20 miles away) and the smaller Blue Stones (brought from the Prescelly Mountains [Mynydd Preseli] in S Wales, about 200 miles away) seem to have been placed to reinforce the Midsummer Sunrise alignment. However, modern opinion is that the builders of the later monument were in fact pointing the stones in the opposite direction! If we consider that the Mid Winter Sunset is 180 degrees from the Mid Summer Sunrise much more of the construction makes sense; a procession up the Avenue, a pause at the Portal Stones and a final entry into the sacred circle and all the time, the object of veneration shining ahead. This is, of course, pure speculation, we can never know the precise thoughts that went through the minds of our far distant ancestors when they built and celebrated in these amazing monuments. On a personal note, while the views of the Midsummer Sunrise from within the circle are certainly amazing, to walk as I did above, toward the Sunset is an experience I will never forget. Jim Mitchell With many thanks to Pete Glastonbury, a professional photographer from Devizes, Wiltshire and an expert on all things stony, who invited me to join him and a small group of archaeo-astronomers to privileged access into the stones and to English Heritage for allowing it to take place.

PHOTO OF THE MONTH COMPETITION: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter. Featured submissions (best of month) will receive a prize of $25 USD. Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.