|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

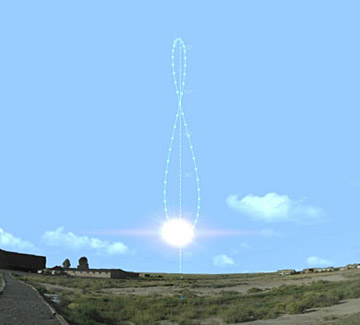

It’s winter in the Northern Hemisphere and we’re at our closest point to the Sun. Closest? Yes, you read that right. Closest. For northerners, the winter solstice has just passed. But the truth is, on January 3, 2007, Earth reaches perihelion, its closest point to the Sun in its yearly orbit around our star. At first glance, it makes no sense. If Earth is closest to the Sun in January, shouldn’t it be summer? Maybe, if you live in the Southern Hemisphere. So what does this mean? Earth’s orbit is not a perfect circle. It is elliptical, or slightly oval-shaped. This means there is one point in the orbit where Earth is closest to the Sun, and another where Earth is farthest from the Sun. The closest point occurs in early January, and the far point happens in early July (July 7, 2007). If this is the mechanism that causes seasons, it makes some sense for the Southern Hemisphere. But, as an explanation for the Northern Hemisphere, it fails miserably. In fact, Earth’s elliptical orbit has nothing to do with seasons. The reason for seasons was explained in last month’s column, and it has to do with the tilt of Earth’s axis. But our non-circular orbit does have an observable effect. It produces, in concert with our tilted axis, the analemma. If you plot the noontime position of the Sun in the sky over a one-year period, it produces a figure-eight shape on the sky (Figure A). This is the analemma. You may have seen it drawn on a globe of Earth. The shape results from the combination of two things: the 23.5° tilt of Earth on its spin axis, and the elliptical shape of Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

Figure A The highest point on the analemma is the Sun’s noon position on the summer solstice. The lowest point marks the winter solstice. The difference in the Sun’s noontime height in the sky is caused by Earth’s tilted axis. What about the left-to-right variation in the analemma’s curve? That’s where our elliptical orbit comes in! Look at Figure A again. Notice the vertical line running up from the south point on the horizon? That’s the meridian. The meridian runs straight up and over the sky, from due north to due south.

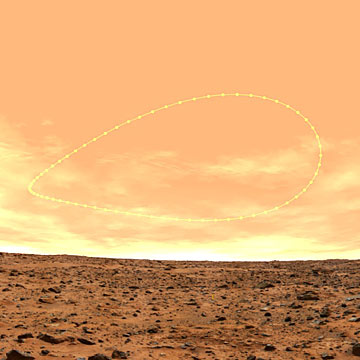

Figure B—Mars is tilted with respect to the plane of its orbit, just like Earth, only a touch more, at 25.2°. But Mars' orbital eccentricity is more than five times larger than Earth's. Combined, these facts produce the Martian analemma above. If Earth's orbit was a perfect circle, the Sun would cross the meridian at noon every day (ignoring daylight savings time). But our orbit is slightly oval-shaped. In July, we are at our furthest point from the Sun, and Earth moves slower than average along its path. In January, we are closer to the Sun, and Earth speeds up a bit in its orbital progress. The result of this change in speed means the Sun crosses the meridian a little early, or a little late, depending on where Earth is in its orbit. For all points along the curve to the left of the meridian, the Sun is “slow.” It crosses the meridian after 12:00 p.m. For all points along the curve to the right of the meridian, the sun is “fast,” crossing the meridian slightly before noon. Astronomers call this the equation of time. It is marked on many sundials. The equation of time is defined as the difference between true solar time (determined by the Sun’s position in the sky) and mean solar time (the time told by your watch). The two times can vary by as much as 16 minutes over the course of a year.

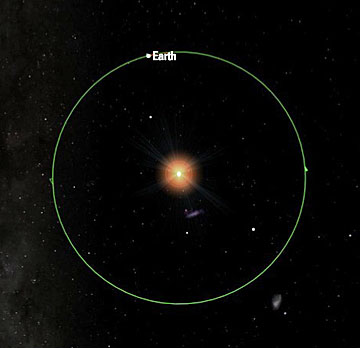

Figure C Just How Close is Close? Earth reaches perihelion on January 3, 2007 (Figure C). The Earth-Sun distance will be 147,093,602 km. Aphelion, the greatest distance from the Sun, occurs on July 7, 2007, when the Earth-Sun distance will be 152,097,053 km. The difference between the two is 5,003,451 km, (3.3 percent), and not enough to cause the seasons. Even though, at this time of year, we're as close to the Sun as we can get, for the Northern Hemisphere, it will always be winter. Happy perihelion! Mary Lou Whitehorne

For those of us who live in northern climes, winter astronomy is a mixed blessing. Some of the finest objects in the sky are best placed in winter time, but the cold weather often keeps us from enjoying them. In this article I’ll give some tips for winter observing, and then highlight some of the sights that will make it worth braving the cold. Preparing yourself Crisp winter days can be enjoyable when the Sun shines brightly and you can walk/ski/snowshoe briskly. It’s a different matter standing or sitting very still peering through an eyepiece under a winter night sky. The first thing to do is to dress warmly, in layers, in order to retain your body heat. Because astronomy doesn’t involve much physical movement, you should dress as if the temperature was at least 10 degrees colder than predicted. The clothing sold for other winter outdoor activities serves very well. I recently discovered jeans lined with flannel at a work clothing store, which serve well on milder nights; I have a fully insulated one-piece boiler suit for really cold nights. A warm hat is especially important, as we lose much of our body heat through our head: I usually wear a wool watch cap. On really cold nights, a ski mask or balaclava is really welcome. It’s also important to keep your feet warm: cold feet will kill your observing interest faster than anything else. Insulated working boots will do the trick, but it also helps if you put down an insulating mat under your observing area. There are some serious safety concerns in winter observing. Hypothermia can creep up on you very subtly. If you’re observing from a remote location, always use the buddy system, and make sure your buddy has his own car, in case you have trouble starting yours. I prefer observing close to home, where I can step inside every hour or so to warm myself up. Be very careful around the metal parts of your telescope: it’s extremely easy to freeze your flesh to any exposed metal parts of the scope. If it happens, warm things gradually and separate with great care. A warm beverage in a thermos can help to keep you comfortable, but avoid caffeine and especially alcohol. Preparing your telescope Most telescopes are manufactured in parts of the world warmer than where we live. The only telescope I own which seems really happy in winter is my Russian-made Maksutov-Newtonian, which seems to feel right at home at sub zero temperatures! Telescopes give trouble in two specific areas: lubrication and batteries. The lubricants used in telescope mounts, focusers, etc. turn into glue at low temperatures. It’s best to strip off the supplied lubricant and replace it with the lithium-based greases designed for snowmobiles. Batteries depend on chemical reactions to generate current, and chemical reactions go more slowly at lower temperatures. Generally, the smaller the size of the battery, the sooner it will fail at cold temperatures. I often store my telescopes in an unheated garage or shed, but I always store the batteries inside my heated house. The little AA and 9v cells used in most astro equipment are next to useless below freezing. If you’re close to home, use an AC adapter to power your equipment. If you’re in the field, look into the “power tanks” sold by many astronomical suppliers. But before spending a lot of money on one of these, check your local auto supply store for less expensive alternatives. Once again, the larger the physical size of the battery, the longer it will last, and be sure to store it indoors on a trickle charger. It may be tempting to run your equipment off your car’s battery, but you don’t want to find yourself with a dead battery when you want to head home. It’s best to store your telescope in an unheated garage or shed, rather than subjecting your scope to drastic temperature changes, plus the heavy condensation which can occur when you bring the scope indoors. If you must bring a very cold scope indoors, cap it tightly while still outside to minimize internal condensation. The same applies to eyepieces and other accessories. The rewards! Is it worth going to all this trouble, rather than staying indoors and viewing Hubble images on the internet? Definitely! Some of the sky’s finest sights are overhead in wintertime.

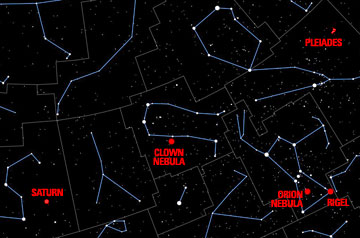

The Orion Nebula (Messier 42 and 43) This is without argument the finest emission nebula in the sky. It is easily found as the middle “star” of the Sword of Orion, hanging below his famous Belt. This is a fantastic site in even the smallest telescope, and only gets better the larger your telescope’s aperture and the darker your sky. Try it with every eyepiece you own, with and without a nebula filter. Every view is different, and every one rewarding. I can easily spend an hour or two exploring this wonderful object on any clear night. Try to trace the outermost tendrils of its two widespread arms. Then put on your highest magnification and see how many stars you can see in The Trapezium, the glorious multiple star at its core.

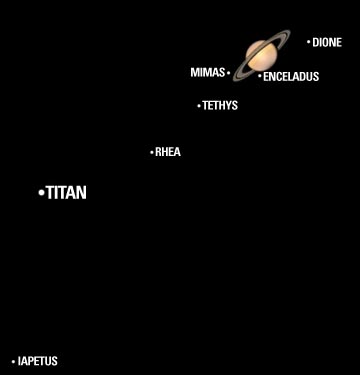

The four brightest stars are pretty easy, but can you spot the elusive fifth and sixth stars? These require good optics and a dark sky, as they are buried in the glow of the surrounding gasses. Rigel This is one of my very favorite double stars. I discovered it quite by accident one night when I was testing a new telescope. I was looking for a bright star to use for a star test, and chose Rigel. When I cranked up the magnification, I was amazed to discover than Rigel was not alone, but had a tiny white speck of a companion. Though actually a white dwarf, this star gives the impression of a tiny planet circling a brilliant star. This discovery started me on a quest to observe double stars, for which I used the wonderful list of a hundred doubles recommended by the Astronomical League: Double star observing used to be a mainstay of amateur astronomy, but got shoved aside by deep sky observing for many years. Recently it seems to be enjoying a comeback with several new books published on the subject. Eskimo or Clown Nebula (NGC 2392) Summer may have its Ring Nebula and Dumbbell Nebula, but winter’s Eskimo Nebula will challenge both of these as the finest planetary nebula in the sky. Located close to the fine double star Wasat (Delta Geminorum), it is easily mistaken for a star at low power because of its small size and brightness. The Pleiades (Messier 45) The brightest and one of the closest open star clusters in our neighborhood, The Pleiades makes a fine sight on a crisp winter night. How many stars can you see with your naked eye? Most people can see six, but more can be detected with careful observation. Because of its large size, this cluster is best viewed with binoculars. Under really dark skies, see if you can detect the faint nebulosity which envelopes this cluster. Don’t be fooled by haze in our own atmosphere. A good test is to compare the view with the nearby Hyades, which have absolutely no nebulosity associated with them. Saturn I saved the best for last! Saturn is now rising in the mid-evening, and is a treat for all astronomers. This planet can tolerate as much magnification as your telescope is capable of, so don’t hold back. Look for the shadow of the rings on the planet and vice versa. See if you can detect the hairline Cassini division between the two main rings; how far around the ring can you follow it? Try to spot the faint inner Crepe Ring, most easily seen against the background of the planet, but sometimes visible against the sky. Can you see any belts on the globe, or its greenish polar region? Scan the area around Saturn for its moons. Use Starry Night® to print a map of their locations. Titan is easily seen in any telescope. Rhea is more of a challenge and Tethys and Dione require a good eye and telescope. Iapetus follows an odd orbit, and changes in brightness as it moves from west to east. Enceladus is extremely challenging, and tiny Mimas just about impossible.

So remember: Dress warmly, be prepared, and enjoy the wonderful sights of the winter sky! Geoff Gaherty |

JAN 2007

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Starting July 1, 2007, Arkansas teachers can use state funds to purchase Starry Night® Middle School at special prices from their local depository. Starry Night® Middle School has already been adopted by New Mexico, and California has deemed Starry Night® Middle School to be compliant. Case studies have proven Starry Night® to be effective in teaching space science concepts. For more information about Starry Night® Middle School and other Starry Night® Education products, please contact Mike Goodman at (952)653-0493 or mgoodman@space.com Linda Fung |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Thirteen/WNET & WLIW21 Celebration of Teaching & Learning's JPMorgan Chase "Multimedia in the Classroom" Awards Competition, sponsored by JPMorgan Chase, recognizes innovative and effective practices and projects that demonstrate how learning can be improved in the K-12 curriculum in science and global awareness through the use of multimedia and technology by teachers and students. This would be a great opportunity to share resources you may have created using Starry Night® that makes effective use of multimedia and technology in support of science and motivates K-12 students and their teachers to explore learning possibilities. Prizes Include:

K-12 teachers and students in public and non-public schools in the tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut) are eligible to participate. All entries must be postmarked by 2/2/07. Please also share your entries with us by e-mailing photo@starrynight.com For more information, visit |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Download your FREE Starry Night® version 6.0.3 Update The FREE Starry Night® version 6.0.3 update is now available for download. We've made over 20 optimizations since the 6.0.1 update in October, including:

If you already own Starry Night® version 6, it's easy to update to version 6.0.3

Please be patient as there may be a number of people downloading at the same time. There's never been a better time to upgrade to the new Starry Night® Version 6 As an added bonus, receive $20 instant savings on your purchase of a Starry Night® Version 6 upgrade. During checkout, simply enter coupon code snv603. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Perseus is the mythological hero who saved Andromeda from Cetus, the Sea Monster. Perseus used Medusa's head (lopped off in a previous adventure) to turn Cetus to stone. At this time of year Perseus is visible in the north-east after dusk. As the night progresses, it rises higher for excellent viewing, and there are a number of fabulous sights on show... NGC 869/884, the Double Cluster, is a favorite target and with good reason. Use binoculars to get an overview of this jewel box, then a low magnification in your telescope to bring out the distinctly varied coloration of stars in each cluster. Both clusters are about 7000 light-years away and are part of the Perseus arm, one of the spiral arms of our Milky Way. M76, the Dumbbell Nebula, is another favorite among observers because of its obvious hourglass/dumbbell shape. It's faint and small but responds well to magnification. Averted vision will help you see its two distinct lobes and nebulous wisps. NGC 1245, an open cluster, is best viewed with low magnification. Most of the stars are hot blue, but there are some nicely contrasting bright orange stars, cooler and older than their blue house mates. M34, another star cluster, contains about 60 members including several double-stars. The cluster is 1,500 light-years distant and is moving in the same direction through space as the Pleiades. NGC 1023, an very elongated looking galaxy, hangs in space roughly 30 million light-years from the back of your eye. From that distance it's surprisingly bright, especially the middle. Try all magnifications to pick out structure and details. NGC 1499, the California Nebula, is a large emission nebula. Under dark skies, it's bright enough to see with the naked eye. Use low magnification and a nebula filter if you have one. See if you can make out the shape of the state that gives the nebula its name. Sean O'Dwyer |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Thin Crescent Moon taken by Ken Stewart, West Haven, Utah with a Fuji Finepix S700 Digital Camera. The ISO was 200 and the exposure 1/2 second.

PRIZES AND RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter.

Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.