|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

Highlights of the test report include: What We Like

"The freedom from worry over tangled or twisted wires is a real pleasure." "Operating a telescope with planetarium software on a computer, rather than the telescope's hand controller, gives you more information. You typically see a star chart showing where in the sky your scope is pointed and what other objects of interest might be nearby. Click on an object anywhere on the star chart, and off the scope goes to find it. And now, thanks to the BlueStar, this can happen without any worry of a connecting cable wrapping around the spinning scope. Hooray!" "[T]he BlueStar is a welcome turnkey solution to wireless control with laptop computers. It makes controlling the scope that much easier, with no intervening wires to trip over or tangle in the dark. Once you use the BlueStar you won't go back to wired astronomy again." Alan Dyer tested BluteStar with planetarium software other than Starry Night. BlueStar also works with Equinox version 6.1.2 and SkyChart III version 3.6.4 on the Mac. On Windows, it works with Cartes du Ciel version 2.7.6, Earth Centered Universe version 5.0, MaxIm DL version 4.53, MegaStar version 5.0.12, SkyMap Pro version 10, and TheSky Version 6. For the full review, see the March issue of Sky & Telescope on newsstands Feb. 6!

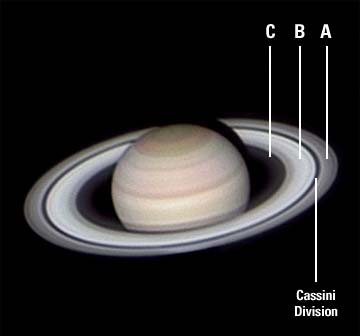

Riding the ecliptic near Regulus, Saturn is now prominent in the eastern evening sky as it heads to opposition February 10th. It will move slowly eastward, remaining the brightest star in Leo for the next two years. My first glimpse of the ringed planet through a friend’s telescope many years ago got me hooked on this hobby. Decades later, an encounter with Saturn on a steady night still takes my breath away. For the astro-photographer, a sharp and detailed image of Saturn is a prized and elusive catch. The ringed planet is a tough subject, revealing its treasures only in good conditions. The delicate disk bands and concentric minima in the B and C rings demand smooth, well-collimated optics and steady seeing. You also need to shoot at high magnification (a long effective focal length.) Saturn is small, spanning 45 arcseconds across the rings with a disk only 20 arcseconds in diameter. The Cassini division, a gap large enough for our moon to pass through, measures a scant arcsecond at best. This represents a speck about half the width of a red blood cell at the focal plane of a 4” f6 telescope! And the holy grail of Saturn imaging, the razor thin Encke gap, is much smaller. Though beyond the theoretical resolution of amateur scopes at a twentieth of an arcsecond, the very best images will show its location in the outer region of the A ring.

Saturn image courtesy Alan Friedman

It's easy to find viewing opportunities for Saturn using the Event Finder in the new Starry Night® version 6. 1. Open the Events Tab. Practice and experience will help you determine the best telescope set-up and camera settings. I use a B&W streaming camera (an industrial webcam) for planetary imaging. A barlow extends the focal length of my 10” f 14.6 scope to 11 meters, placing a large Saturn on the 640x480 chip but still leaving some wiggle room for drift during the exposure. Sky transparency will determine the shutter and frame rate (between 15 and 30 frames per second). Camera settings are a juggling act, balancing image brightness with electronic amplification (more commonly called gain) – increasing the image brightness with a high gain setting will create a noisy image. These B&W video streams provide the detail (luminance) for my final LRGB image. Color data is captured with the same camera using RGB filters. The filters consume light (hence the lower sensitivity of color cameras.) I often reduce the focal ratio to f30 for the filtered capture. The image will be smaller, but I can scale the color data to match the luminance data later on, combining both in Adobe Photoshop to construct a full color image. Experimentation will determine the right Barlow and image scale for your telescope, mount and camera. If the image is too dim, focusing too difficult, or if tracking makes it hard to keep the image on the chip, move to a lower magnification. Sensitive image processing will reveal the detail in your recorded data. Using software programs like MaxIm DL and Registax, or the Mac based application Astro IIDC, you can select and stack just the sharpest frames from your video streams. This magical process will increase the signal, average out the noise, and display features not visible in the individual frames. These programs allow you to select an alignment position for the frames in your stack. This can be a powerful advantage. On most nights, even the best frames in your stream will not be uniformly sharp throughout the image. One side of the rings might be sharper than the other. By processing the image multiple times using different alignment positions and then combining these optimized regions with mosaic techniques in Photoshop, you can create a seamless composite that records maximum detail from your session. As a final step, image processing with software tools such as wavelets and unsharp mask can be used to increase contrast in the image. Your personal taste and end purpose will guide you here. I prefer a natural feel and so I use a restrained hand with these tools. Overdoing it will introduce artifacts in high contrast areas of the image - along the edge of the disk and in the rings and ring gaps. It will take practice, but a detailed image of Saturn with its glorious ring system etched against the velvet blackness of space is a prize worth the effort. Alan Friedman

The poet Walt Whitman said, “I do not want the constellations any nearer, I know they are very well where they are.” But where are they, exactly? Constellations cover the sky. They also look flat - the stars all appear to be at the same distance. Appearances can be deceiving. We often refer to stars that look bright as “big,” and to their fainter companions as “small” stars. Are the bright ones really big? Are the faint ones actually small? Maybe the bright ones are closer and the fainter ones are farther away. Could it possibly be any other way? This is astronomy so the answer is “yes!” The distance to any celestial object is one of the most important things we can know about it. Without that single critical piece of data, everything else is almost meaningless. To understand the structure and organization of things celestial, we must know distances. The Hipparcos satellite has provided us with accurate and precise stellar distances, revolutionizing our picture of the universe. With Starry Night® it’s easy to find distances to individual stars. In doing so, we discover that some nearby stars are dim, and some bright stars are nearby. We also find that some of the brightest stars are very distant. When a distant star is also a bright star, it means the star is highly energetic; shining with hundreds or thousands of times the output of our Sun!

Figure 1—Some stars in the constellation Orion are much further away than others. At this time of year, a prominent constellation is Orion (figure 1). Orion hosts some of the brightest stars in Earth’s sky. Are they near or far? Table 1 tells us Orion’s stars lie at distances ranging from 243 to 1,360 light years. Rigel is brightest with a magnitude of 0.2. (Magnitude describes brightness. The lower the number, the brighter the star.) Rigel is 777 light years away and 51,000 times as bright as the Sun. Bellatrix is closer at 243 light years, fainter at magnitude 1.6, and only (!) 6,000 times as luminous as our Sun. Table 1. The Stars of Orion

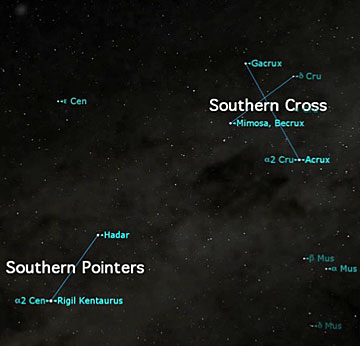

Table 2. The Stars of the Southern Cross

Table 2 shows information for stars in the Southern Cross (figure 2). Notice Rigel Kentaurus, also known as Alpha Centauri, our nearest stellar neighbor. It is bright at magnitude -0.04, and lies 4.4 light years away. But it has only twice the luminosity of the Sun. Now you know why we can’t begin to understand stars until we know their distance.

Figure 2—The stars of the Southern Cross and Southern Pointers vary in distance, but not over as great a range as those of Orion. To really get a grip on stellar distances, we have to build a scale model. Try it. It’s easy! Assume your doorstep is the Sun, and one step represents one light year. Start walking the distances to the stars in the Southern Cross or Orion. Four steps will take you to Alpha Centauri. The Southern Cross stars will have you strolling from 88 to 364 steps, or roughly 70 to 300 metres. Orion will give you more exercise. You’ll take 243 steps (200 m) to get to Bellatrix. Walking to Alnilam will take 1,360 steps. By then you’ll be about 1 km from your door! Try this with friends or a school class. With one person for each star, you’ll soon have a 3-D constellation model that is definitely not flat. The stars in a constellation are not bound to one another. They are random groupings of stars upon which we have imposed recognizable patterns. Different cultures have created different (and equally valid) constellation groupings. Astronomers have established 88 officially recognized constellations. These are based on the classic Greek and Roman star patterns, with boundaries defined by a celestial coordinate system. A constellation’s stars may lie in the same direction on the sky, but they are not connected to one another. Any star visible to the unaided eye can be anywhere from a few to a few thousand light years distant. The constellations are indeed very well where they are: extending far into the reaches of the starry night sky. Enjoy their distant light! Starry Night® Education Extensions for Constellations For more lesson plans on constellations, refer to the "Star Finding and Constellations" unit in Starry Night® Middle School and High School. Lesson Plan G1, The Solar Neighborhood, in both Starry Night® Middle School and High School offers hands-on activities and computer exercises to illustrate the vast distances between stars. Lesson Plan G2, The Stars, explores the nature of stars. This Lesson Plan in Starry Night® High School also includes a worksheet that allows students to collect data and create their own Hertzsprung-Russell diagrams. Mary Lou Whitehorne

Very soon after the first telescope was invented, someone got the idea of mounting two telescopes side by side. We are, after all, creatures with two eyes, and tend to see more, and be more comfortable, when using both our eyes. Originally called “field glasses,” because of their military applications, they soon became adopted by nature lovers and amateur astronomers. In the late 19th century opticians started adding prisms to the design, resulting in more compact instruments with wider fields of view, and these instruments became known as “binoculars.”

Although binoculars do impart a mild three-dimensional view to nearby objects, when used for astronomy any such effect is an optical illusion, though sometimes a powerful one. The main advantage for an amateur astronomer in using binoculars, rather than a small handheld telescope, is that they are relatively easy to hold steady, and the images often seem brighter and more detailed because of the image processing which goes on in our brains when presented with two channels of information. Binoculars are extremely easy to use, and make scanning the night sky a pleasant intuitive activity, without the need to fiddle with finders, mounts, and eyepieces. In some ways, binoculars “don’t get no respect.” They’re often looked down on as the astronomical telescope’s poor relation. Yet they are a fine instrument in their own right, capable of observing objects which are simply too big to see properly in a telescope. One of the few astronomers to take binoculars seriously is Phil Harrington, whose book, Touring the Universe through Binoculars (Wiley), is the bible of binocular astronomy. They are also, to serious deep sky observers, an essential accessory in discovering starhopping paths through the stars. Many households already have a pair knocking around, or a reasonably good pair can be found at most sporting goods stores, so they are an inexpensive way to get started in exploring the sky. Numbers and more numbers Binoculars have a numbers game all their own. Different types are described by a pair of numbers with an “x” in between: 7x35, 10x50, 20x80, etc. The first number is the magnification: 7 times, 10 times, 20 times. The second number is the aperture of each half of the binocular in millimeters: 35 mm, 50 mm, 80 mm. They usually will be labeled with a field of view, either in degrees or how many feet they will show at 1000 yards (one of the strangest units I know of!) Another important number is their “eye relief,” which measures how far behind the eyepieces you must put your eyes to catch all the light. If you need to wear glasses while using binoculars, choose a pair with at least 15 mm eye relief. Finally, there is their “exit pupil,” the diameter of the cylinder of light coming out the back of the binoculars. This is calculated by dividing the aperture by the magnification; it’s a very important number, and I’ll say more about it later. Other factors I mentioned that all modern binoculars have prisms in their optical design. These are of two different kinds, but both serve the same purpose, to turn right side up the telescope’s typical inverted image. Porro prisms give many binoculars their characteristic “Z” shape; they are relatively simple to make and pass light well. Roof prisms result in “straight through” optical tubes: more compact, but also more expensive to make and, until recently, less efficient at passing light. The glass from which the prisms are made also has an effect, better binoculars using BAK-4 glass. A quick way to check a binocular in a store is to hold it about 15 to 20 inches away from your eyes and look at the exit pupils (the circles of light leaving the eyepieces). If these are clean circles, the binoculars have good prisms; if they’re cut off into a diamond shape, the prisms are too small or made from the wrong glass. Most optical instruments nowadays have their glass to air surfaces coated to reduce reflection and increase light throughput. But binoculars differ in how many surfaces are coated and with what kind of coating. “Coated” by itself means little; “fully multicoated” means that all glass to air surfaces are coated with multiple layers of coating. Because binoculars have two telescopes, there must be a way of focusing them independently, because most peoples’ eyes differ a bit from left to right. The best binoculars allow both halves to focus together, while one eye has an independent adjustment. Avoid at all costs binoculars labeled “fixed focus” or “universal focus” as these will be poor performers in general, and totally useless for astronomy. Binoculars on your computer It's easy to select objects for binocular viewing. Users of Starry Night® Pro 6 and above can easily add field-of-view indicators to their Starry Night® display.

To turn the outline of the indicator on/off, simply check/uncheck the box to the left of the indicator box where it appears on your equipment list. Starry Night® will simulate what you might be seeing through various binoculars and will help you determine which binoculars might be best for the objects you're hunting. Binoculars for astronomy

If you look through Orion’s web site, you’ll see 50mm binoculars at a variety of prices and two main magnifications: 7x50 and 10x50. Which magnification? It depends on your age. As we grow older, our eyes lose their ability to open wide. Someone under 30 years old usually has eyes which can accept an exit pupil 7 mm in diameter, such as a 7x50 binocular provides. Someone over 50 years old has eyes which won’t open much above 5 mm, so a 5 mm exit pupil, such as a 10x50 produces, will be more suitable. Another factor comes in as well: with a bit more magnification, the sky background will be darkened more and the magnification boost will make small objects easier to see. For that reason, I generally recommend 10x50 as the best size for general astronomy use. So, what about the different prices? With binoculars, you pretty much get what you pay for. The more expensive models are generally better made from more expensive materials, and will generally last a lot longer. A good compromise on an entry level binocular is the Orion Scenix. A few years ago, I decided to treat myself to a somewhat better binocular, and bought a Celestron Pro 10x50, which has become my constant observing companion. Celestron discontinued that model, but its twin lives on as the Orion UltraView. Here there be giants! While 10x50 binoculars are probably the most useful everyday tools for most amateur astronomers, some of us get hooked on the two-eyed view, and long for something bigger and better. Yes, aperture fever lurks in the world of binoculars too! When you move to giant binoculars, you lose a bit of the easy hand-held use of small binoculars, though the performance of any binocular can be improved by mounting it on a tripod. But what views you gain! My first giant binocular was an Orion Little Giant II 15x70. Despite its size, this binocular is remarkably light in weight and very well balanced, so that I found I could use it while sitting down and braced without a tripod, almost as convenient to use as my 10x50s. I particularly like taking this binocular with me when traveling to southern destinations. Recently I had the opportunity to try out the giant of giants: an Orion GiantView 25x100 Explorer. Although it says “Tripod optional” in the photo, don’t believe it! These are two 4-inch refractors linked together on a solid longitudinal axis, the whole unit weighing in at over ten pounds. They come packed in a solid carrying case, and are absolutely gorgeous to look at. But it’s the views through them which are really astounding. The unit I tested had been kicking around the Starry Night® office for a while, and Pedro hesitatingly said they might be out of collimation. Collimation? I’ve collimated my Newtonian reflectors many times, but had always believed that binocular collimation was something which required special tools. However, a little research on the internet indicated that giant binoculars like this are very sensitive to misalignment, but quite easily put right once you know the secret. The secret is to find out where the adjustment screws are located. My first look through the binocular confirmed that things were out of whack: the two images were out of alignment beyond anything my eyes could accommodate. My internet guide told me that the adjustment screws were hidden beneath the rubber grip on the prism housings, just in front of the name plates. Prying the rubber up with a screwdriver revealed the screw heads, and some scratches that showed that I wasn’t the first person to venture into this region. It seems that, in the land of the giants, collimation is pretty routine. Collimation is done in daylight with the binoculars focused on a distant object, moving your eyes back from the eyepieces and then forward again, tweaking the screws gently, until the two images merge cleanly and comfortably. Not all that hard really. Once collimated, the views were outstanding. I concentrated on really large objects under my dark country skies, and was especially impressed with the Andromeda Galaxy and its two companions, the Pleiades, and, especially, the Double Cluster in Perseus. The latter gave the illusion of three-dimensionality which makes these binoculars so addictive. The heavy axis joining the two halves has a sliding tripod adapter on it, making balancing these giants on a tripod very easy. The only difficulty is that at 25 power, it’s sometimes hard to point them accurately. I’ve heard of people mounting unit-power finders on them to get them pointing in the right direction! Geoff Gaherty |

FEB 2007

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The FREE Starry Night® version 6.0.4 update is now available for download. The 6.0.4 Update includes:

If you already own Starry Night® version 6, it's easy to update to version 6.0.4 You must be connected to the Internet to receive the update. Download the installer by checking for updates.

Run the installer. When you launch Starry Night®, you will have version 6.0.4. Please be patient as there may be a number of people downloading at the same time.

Linda Fung Last week favorably placed observers viewed a comet so brilliant that it could be seen with the naked eye in broad daylight, if the Sun was hidden behind the side of a house or even an outstretched hand.

Image © Robert McNaught, 2007 Comet McNaught, which was discovered last August by astronomer Robert McNaught at Australia’s Siding Spring Observatory, was one of the greatest comets in recent times. It evolved into a brilliant object as it swept past the Sun on Jan. 12, at a distance of just 15.9 million miles. Joe Rao |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At Mag -1.5, almost everyone knows that Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. You may notice it driving home from work: visible from early dusk, it sparkles brilliantly above the southern horizon. What many people don't realize is that Sirius is actually a double star. Sirius B is a challenging target, just 5" from Sirius and quite dim at Mag 8.5. It requires excellent optics but, if you can nail it, it's surely a feather in your cap. A little to the west of Sirius is a three star asterism, with the central star, V1, being an easy, pretty double separated by 17". M41 (also known as the Little Beehive) is a fine open cluster lying about 2,000 lightyears from the back of your eyeball. It has about 25 bright stars spattered across a field about the size of a full moon; in reality, they're spread over an area 20 lightyears in width. Bright enough to be sometimes visible to the naked eye (Aristotle is said to have noticed it around 325 B.C.) M41 is a good target for binos or low magnification in your scope. M46 and M47 are two open clusters just over 1° apart, making comparison very easy. Both are about 20 million years old but they're not connected in any way: M46 hangs in space about 5,000 lightyears distant, while M47 is closer at 1,700 lightyears. Of special interest is the planetary nebula that seems to be embedded near M46's center. Although the nebula is probably not actually part of the cluster (it simply lies along the same line of sight), it makes for a good opportunity to see two different types of deep sky object at the same time. In larger scopes, NGC 2360 (a.k.a. Caldwell 58) is a pleasing open cluster almost half way between M46 and Sirius. M93, the winter Butterfly Cluster, is a rich 6th Mag open cluster with about 80 visible stars. It's core resembles an arrowhead. While you're in the area take a look at k Puppis, a nice bright double. NGC 2362, the Mexican Jumping Star (a.k.a. Caldwell 64), and NGC 2354 are another pair of closely placed open clusters worth comparing. Finally, Mag 1.5 Adhara has a Mag 7.5 double just 7.5" due south. Adhara is a main sequence star that shines 9,000 times as brightly as our own sun. Good thing it's 432 lightyears away. Sean O'Dwyer |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Rosette Nebula Taken by Phillip Holmes using a STL-11000M camera on a G11 mount and a Televue NP101mm F5.4 telescope from his backyard in Rockhampton Australia.

PRIZES AND RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter.

Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.