|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

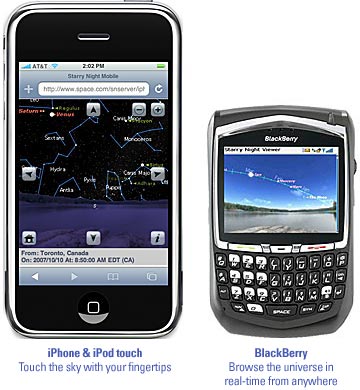

Starry Night® is now available on your portable handheld device. Using a simple and intuitive interface, view the stars, planets, constellations and more from any location on Earth.

Downloading and Installing iPhone and iPod touch Have an iPhone or iPod Touch? Visit the following URL: Blackberry Find out how to download the Starry Night® BlackBerry application at the following URL: Pedro Braganca

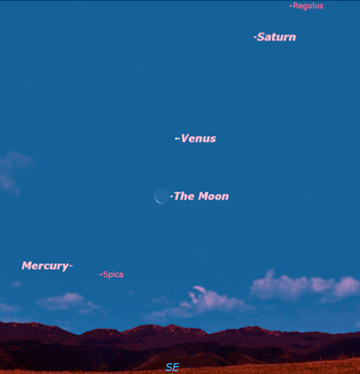

Back in April 1996, Stephen James O’Meara suggested in Sky & Telescope that we hold occasional solar system marathons when all of the planets are visible. Right now happens to be one of those times. It’s a fun challenge for any observer, no matter what their equipment. The idea is to observe as many solar system objects as you can in a 24 hour period, giving yourself one point per object. The total possible scores depend on whether you’re using naked eye, binoculars, telescopes, or imaging. The Sun The Sun counts as a solar system object... heck, it’s the most important object in the solar system! You should never look at the Sun without some sort of protection: a #14 welder’s glass or “eclipse shades” from a telescope store for naked eye, and a full aperture solar filter for binoculars and telescopes: Give yourself a bonus point if you see a sunspot (pretty rare right now because we’re near solar minimum) or a flare or prominence (visible only with special Hydrogen Alpha filters). Planets Mercury is at greatest elongation west (19° from the Sun) on November 8, and is well placed for observation at dawn by observers in the Northern Hemisphere for about a week on either side of that date. This is one of the more challenging targets for all observers, but, once you spot it in the dawn sky, it’s easy to track it up into full daylight, when the blue sky will kill the planet’s glare, the higher altitude will improve seeing, and you should be able to see the planet’s shape very well. One bonus point if you can see the phase of the disk. Here’s what Mercury will look like on the morning of November 6, along with Venus, Saturn, the Moon, and the bright stars Spica and Regulus:

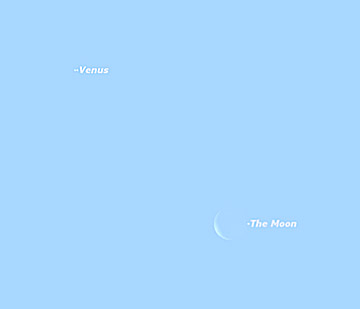

Venus is the brightest object in the sky after the Sun and Moon, and is putting on a brilliant show high in the dawn sky before sunrise. You get a bonus point for seeing its phase (just visible in binoculars) and another bonus point if you can spot it in the full daytime sky. This will be easy to do on the morning of November 5, when Venus will be only a few degrees away from the waning crescent Moon; this is how they will look in 10x50 binoculars:

Earth: Sure, you can count the Earth! Just look down at your feet, and give yourself a point. Mars: Mars is now rising around 9 p.m. and dominates the southern sky for the rest of the night. Give yourself a bonus point if you can detect telescopic features like its gibbous phase, polar cap, or dark surface markings. Major challenge points for spotting either of its tiny moons, Phobos or Deimos; an occulting bar in the eyepiece is essential. A useful aid in spotting Mars’ elusive surface markings is a good set of filters especially designed for Mars: This set includes a No. 21 orange filter, best for all around viewing of Mars, a No. 82A blue filter, best for seeing clouds and other atmospheric features, and a special new Mars interference filter, which emphasizes surface and atmospheric features while cutting glare from the middle of the spectrum. This is the modern equivalent of the famous magenta filter loved by Mars observers but long unavailable. Jupiter, the largest of the planets, will actually be one of the most difficult to see, because it is rapidly disappearing into the glare of the setting Sun. Get it while you can low in the southwest just after sunset, and give yourself a bonus point if you see any detail on the disk. Each of its four bright moons is of course worth a point each. Saturn rises around 1:30 a.m. and is visible the rest of the night. Saturn’s famous rings are rapidly narrowing, and will be playing hide and seek with the Earth next year. Give yourself a bonus point for seeing the rings, and of course a point for each of its moons which you can positively identify on a Starry Night chart like this:

These are the six moons most commonly seen in amateur telescopes, but be sure to try for some of the fainter moons; they all count. Uranus: If you have really dark skies and good eyes, you may be able to see this with your naked eye; otherwise you’ll need binoculars or a telescope. Starry Night comes in handy to make a customized finder chart for Uranus on the night you’re looking for it.

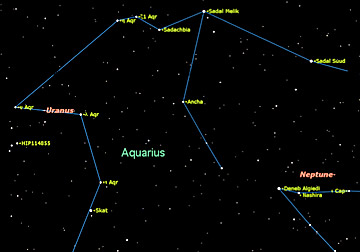

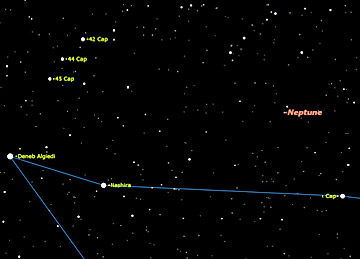

Several of Uranus’ moons are within visual range of larger amateur telescopes, and are also targets for astro-imagers. Neptune is more of a challenge than Uranus, because it’s two magnitudes fainter and much smaller in diameter. You will need a more detailed chart, like this one for November 6:

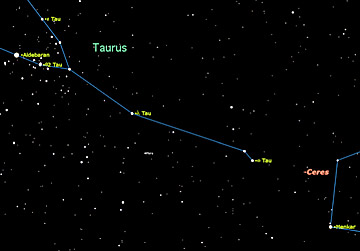

Neptune’s brightest moon, Triton at magnitude 13.5, is actually easier to see than any of Uranus’ moons, but the rest of its moon’s are photographic objects only. Pluto, thanks to the I.A.U., is no longer a planet but you can still get a point for it as a dwarf planet and/or Kuiper Belt Object. A good Starry Night chart is essential, and be sure to download faint stars. Located just north of Jupiter, Pluto will be a challenge because of twilight and low altitude. Ceres: Speaking of dwarf planets, Ceres reaches opposition on November 9 between Taurus and Cetus. The V of the Hyades points to a chain of stars which leads directly to Ceres, easily visible in binoculars at magnitude 6.9:

Comets: Prospects are not very good for most observers. Comet LONEOS (C/2007 F1) should still be visible in telescopes for southern observers, as will be a couple of very faint comets further north, McNaught (P/2007 H1) and Lovas (93P). These require a large aperture, or else can be imaged. The Moon The Moon is certainly worth at least one point, especially since it will require a bit of effort to observe in early November. That’s because it is will be New on November 9, so only visible low in the dawn sky before sunrise. Of course, it will rise with the Sun, and be visible all morning. You’d be surprised how many people are unaware that the Moon is often visible in full daylight! Those with binoculars and telescopes should try to identify by name some craters on the Moon’s surface: one bonus point per crater identified. Even with the naked eye, you can identify some of the larger lunar topographic features. Many people find the Moon very bright to look at. It really isn’t very bright; it’s just that it is in full sunlight while the sky is usually dark, as is the observer’s location. One way to overcome this brightness is to light up your observing area, or at least use a white flashlight to consult your map of the Moon. Another trick is to use a high magnification. The Moon can tolerate higher magnifications than any other astronomical object, so don’t be afraid to push your telescope to 200x or 300x. This may require a new eyepiece or at least a Barlow lens; the Orion Shorty Plus Barlow lens is one of the best available: Smaller solar system objects Finally, let’s not forget the smaller members of the Sun’s family. Meteors: Meteors, popularly known as shooting stars, are small particles which enter the Earth’s atmosphere and disappear in a brilliant flash of light. A bit of time spent under dark skies, especially after local midnight, will almost always show a meteor or two. Add a point if the meteor can be traced back to the constellation Taurus, making it a member of the South Taurid meteor shower, which peaks on November 5. Interplanetary dust: Early November is a good time to look for the Zodiacal Light in the pre-dawn sky. This ghostly light, fainter than the Milky Way, comes from light reflected from millions of tiny interplanetary particles. It is cone shaped, centered on the point on the horizon where the Sun will rise. Rarer still is the Gegenschein, a concentration of interplanetary dust located directly opposite the Sun in the midnight sky. That’s worth another point. Aurora: The aurora is the visible result of even smaller solar system denizens: charged particles emitted by the Sun and drawn into the Earth’s polar regions by our magnetic field. Like sunspots, auroras are dependent on the Sun’s eleven-year activity cycle, so are currently at minimum, but perhaps we will get lucky! Artificial satellites: There are currently thousands of objects in orbit around the Earth, ranging in size from the International Space Station and the Space Shuttle down to nuts and bolts dropped by spacewalking astronauts. Give yourself a point for each satellite seen and identified; another place where Starry Night comes in handy. So, choose your 24 hour period in early November and see how many points you can score on our Solar System Challenge. Even with only your naked eye, you should be able to score ten or twelve points. With binoculars, telescope, or camera, you can score many more. Good luck! Geoff Gaherty

Lying far from the galactic plane (which contains so much obscuring matter) Cetus, representing the gates of the underworld, is home to many observable galaxies. M77 is a 9th Magnitude spiral galaxy, one of the first recognized spiral galaxies, and the closest and brightest of Seyfert galaxies (their central regions having rather bright nuclei whose light output varies over time and atypical spectra with unusual emission lines). NGC 936 a faint galaxy best viewed with averted vision. NGC 246 a large and reasonably bright planetary nebula (the last breath of a dying star) with an irregular "surface texture". While technically in the constellation Sculptor, NGC 253, the Sculptor Galaxy, is a remarkable spiral galaxy with an unusually high rate of star formation. It's the brightest member of the Sculptor group, a group of galaxies centered around the south galactic pole. A small telescope reveals a long bright haze intermingled with brighter regions and dark lanes. Due to its high surface brightness it takes magnification quite well. Sean O'Dwyer

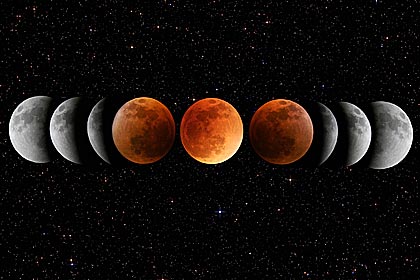

Lunar Eclipse Phillip Holmes from Rockhampton Australia took this beautiful mosaic of the recent Total Lunar Eclipse. The background was taken with STL-11000M on aNP101mm and the moon was taken with a Cannon 30D on the same scope.

PRIZES AND RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter.

Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

NOV 2007

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.