|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

I’ve just returned from a month’s vacation in New Zealand and Australia. The astronomical highlight was four nights spent under pristine skies at the “Deepest South Texas Star Party.” This event, sponsored by the Three Rivers Foundation in Texas, took place at Warrumbungle Mountain Motel, about half way between Siding Springs Observatory and the town of Coonabarabran, in New South Wales, Australia.

Map courtesy Google Maps This was a rather different star party than we are used to in North America. Because of the travel involved for most of us, scopes were provided by the Three Rivers Foundation at the site, including several large Obsession Dobsonians, 18-inch and 25-inch aperture, equipped with Argo Navis digital setting circles and ServoCat goto systems. The observing field was directly adjacent to the motel, which served as a giant warm-up hut. Closely mowed grass made navigating the field in the dark very easy. Below is the 18-inch f/4.5 Obsession I used for most of my observations, with a couple of 25-inch Obsessions lurking in the background.

Naturally, for this expedition into uncharted celestial territory, I turned to Starry Night® for guidance. Needless to say, despite the comprehensiveness of Starry Night®’s database of observing locations, Warrumbungle was not included, so I had to enter its longitude and latitude manually: 149° 11’ 22” E and 31° 16’ 24” S. As soon as it got dark on my first night at Warrumbungle, March 2/3, I cast my eyes south and saw this spectacular vista, here recreated in Starry Night® Pro Plus:

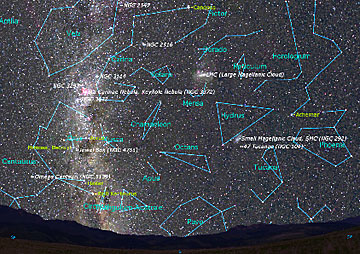

Not much here that I recognized, despite decades of observing northern skies! From a couple of trips south before my serious observing days, I could spot Alpha and Beta Centauri low in the southeast, with the Southern Cross and the Coal Sack just above them, but that was about it. However, Starry Night® soon provided me with a wealth of information:

Most of the southern constellations are forgettable, with the exception of the great star groupings along the southern Milky Way, especially Centaurus, Crux, and Carina. There are few bright stars outside these three, notably Canopus, high overhead, and Achernar at the southern terminus of the great river Eridanus, which can be traced all the way north to Orion. What are absolutely outstanding are the three great galaxies: our own Milky Way, much brighter in Carina than anywhere visible from the northern hemisphere, and our two satellite galaxies, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. As their name implies, the latter two look exactly like small patches of cloud in the dark sky.

This was just the first of four perfect nights. One entire evening was spent exploring star clusters and nebulae within the confines of the Large Magellanic Cloud: a whole galaxy of objects for the picking, culminating in the gigantic Tarantula Nebula. Another night we explored the galaxies and galaxy clusters normally hidden well below my southern horizon. We even observed some “northern” objects. The galaxy Messier 83, which is one of the most difficult Messiers from northern latitudes, usually giving only a glimpse of its small nucleus through the horizon haze, was revealed as a gigantic pinwheel. And I finally managed to see the Horsehead Nebula, with the help of a Hydrogen Beta filter in the 18-inch Obsession. One morning I rose just before dawn to observe the juxtaposition of our “summer” Milky Way in Sagittarius with the “winter” Milky Way of the southern hemisphere, finally managing to visualize the whole of the celestial sphere, north and south. Geoff Gaherty

Last year, astrophysicist Steve Tomczyk of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., and his colleagues asserted that corkscrew-shaped Alfven waves were converting the motion energy of the sun's roiling material into heat. But the authors of the new study argue that the waves Tomczyk's team saw were not Alfven waves but kink waves. "Kink waves look like kinks in hair or rope," said University of Warwick astrophysicist Tom Van Doorsselaere, one of the researchers behind the new study. "Kink waves can't explain why the corona is so hot. They carry less energy with them." Van Doorsselaere said he and his colleagues used a more complex model than Tomczyk and found that the wave observations are not consistent with Alfven waves, and must be kink waves. "At the moment I can't see any other explanation that could explain the observations," Van Doorsselaere told SPACE.com. "I would have wished the other authors were right because it would have been good news to finally solve the problem." The new study was published March 6, 2008, in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. Van Doorsselaere said Tomczyk and his colleagues still think Alfven waves could be behind the corona's heat. "They're not convinced that we are right, but they are convinced that our opinion should be published and discussed," he said. "Probably at upcoming conferences, there will be some lively discussion of this." The sun is not alone in having an inexplicably scorching outer layer. "We think our sun is pretty typical for corona behavior," Van Doorsselaere said. "There are other stars with even bigger and more active coronas." Our sun, being so close to us, provides the best opportunity to study this phenomenon. Scientists still hold out hope we can get to the bottom of the mystery soon. "To test this we need better observations," Van Doorsselaere said. "We're getting better telescopes and satellites to look at the sun. There are several missions coming up to hopefully resolve the problem." He said NASA's upcoming Solar Dynamics Observatory, to be launched sometime at the end of 2008 or beginning of 2009, or ESA's Solar Orbiter, set to launch in 2015, could be the keys to success. Clara Moskowitz

"We have identified asteroids that are not represented in our meteorite collection and which date from the earliest periods of the solar system," Sunshine said.

The scientists observed the asteroids with infrared and visible light telescopes on Hawaii's Mauna Kea. They measured the various amounts of different colors of light reflected from the surface and found evidence that the asteroids contain bits of material rich with calcium and aluminum. An abundance of these elements indicates that the objects were formed when the solar system was young because during that time the first materials to condense into solid particles were rich in calcium and aluminum. These three asteroids contain two to three times the amount of calcium- and aluminum-rich material of any space rock found on Earth. The discovery was detailed in the March 20 online edition of the journal Science. SPACE.com

Everyone knows the Big Dipper (just one section, or "asterism", of the constellation Ursa Major) and most people can easily see that the middle star of its handle, Mizar, has a fainter companion, Alcor. However, aim even a small scope toward Mizar itself and you'll see it's actually two stars separated by 14". A nice easy double. This part of the sky floats above the celestial north pole (which sits very close to the end of the little dipper's handle) so there's much less interstellar dirt obscuring our lines of sight to some interesting, though quite faint, galaxies. M101, the Pinwheel Galaxy, is a difficult spot. A row of stars leads down from Mizar and Alcor to relatively dark area of the sky where two parallel rows of faint stars will help you locate the galaxy's core. Even on a good night, in my 8" reflecting scope M101 is a challenge. A little easier is M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy. This is a rare example of quantity equaling quality: time spent with M51 reaps rewards, with brief flashes of clarity that slowly build in your mind's eye to a fascinating whole. Although faint, two cores are visible; the second, less bright core is NGC 5195, a smaller galaxy interacting gravitationally with its large neighbor. Get your eyes as dark-adapted as possible; averted vision will bring out hints of the spiral arms. M63 and M94 are two more spiral galaxies, less spectacular, but interesting to compare with each other and with M101 and M51. Cor Caroli , the brighter of two stars that make up Canes Venatici, is a nice double even in small scopes. Note the color difference. NGC 4631 is also known, quite properly, as the Whale Galaxy. It's faint, huge, extremely elongated and completely awe inspiring in your eyepiece. NGC 4449 is an irregular galaxy in Canes Venatici. In comparison to the Whale, this galaxy is elongated, kinked, and a bit weird looking. Moving away from some of the fainter targets, M106 is a large and bright spiral galaxy visible in binoculars. Telescopically, it has a large and mottled nuclear region surrounded by a much fainter elongated halo. A larger telescope and dark skies reveals two spiral arms extending from the central region into the halo. At the center of the galaxy is a 35 million solar mass black hole. Finally, M97, the Owl Nebula, is a nice challenge to wrap up an evening's work. A smudge in smaller scopes, larger scopes are said to reveal an owl's-face; whether it does or not is a discussion best taken up with a therapist. Sean O'Dwyer

Eta Carinae shot by Phillip Holems from his backyard in Rockhamton Australia. Taken March 10 with a STL-11000M and 70-200mm cannon lens on a G11 mount. HA/O111/S11 15mins each channel. Shot at about 135mm.

PRIZES AND RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter.

Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

APR 2008

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.

The sun's outer layer, the corona, is inexplicably hot. A new study may complicate things further by poking holes in a leading theory that aims to account for the puzzling phenomenon.

The sun's outer layer, the corona, is inexplicably hot. A new study may complicate things further by poking holes in a leading theory that aims to account for the puzzling phenomenon. The ancient

The ancient