|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For education orders please call 1-877-290-8256. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

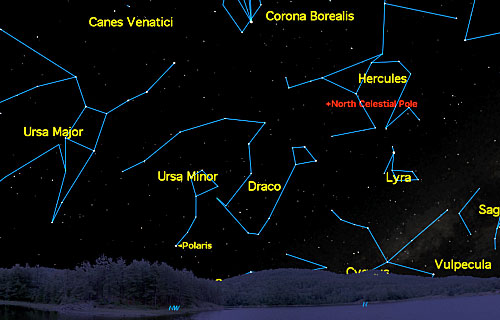

We may not be physically able to travel back in time, but Starry Night can show us what the sky looked like when our ancestors first wondered about those sparkling points of light. Let's jump into our Starry Night time machine and travel back to 35 000 BC. On a warm April night, we gaze at the cloudless northern sky.

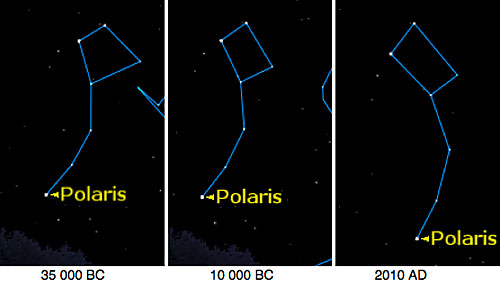

Our familiar constellations are all there. But the Little Dipper asterism in Ursa Minor looks distorted; and the Big Dipper looks odd too. In our excitement we have forgotten that the stars are not fixed in the sky but move at tremendous velocities through space. Because the stars are so far away, their relative motion is usually not apparent for decades or centuries. However, in over 35 thousand years, there is a noticeable change. The screenshots below show the changes in the Little Dipper from 35 000 BC to the present day. Try changing the years using your own copy of Starry Night. What will the Big Dipper look like 50,000 years from now?

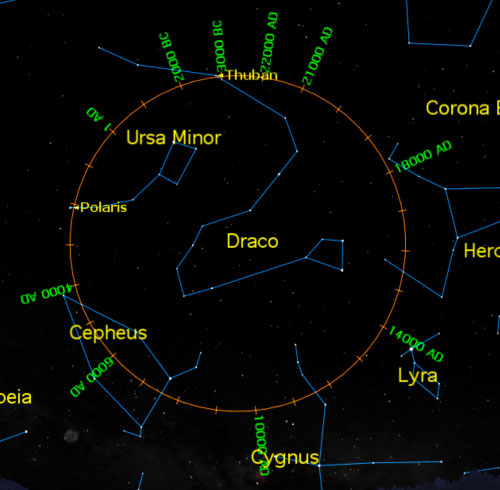

All the screenshots above prominently show Polaris, our pole star, at the end of the Little Dipper's handle. Polaris, of course, gets its name from the fact that it is about one degree from the north celestial pole (NCP). But take a close look at the first screenshot: why is Polaris so far from the NCP? Again, we neglected to take into account a very slow process -- the precession of the Earth's spin axis. We know that this axis is tilted by 23 1/2 degrees with respect to the ecliptic. But like a spinning top, the orientation of the spin axis changes as it slowly traces out a circle. For the Earth, one complete rotation takes about 26 000 years, so the NCP traces out a circle against the background of the stars. Thus in 35 000 BC, no bright star was near the NCP whereas the pyramid builders could use Thuban, in the Constellation Draco, as their north star. Bright Vega will be our north star in about 12 000 years. Check out the screen shot below to see the location of the NCP at various times in the past and the future.

You can also load the file Precession.snf and use your copy of Starry Night to investigate precession. Herb Koller

So, you're interested in learning more about astronomy. So, the first thing you should do is rush out and buy a telescope, right? Wrong! Many people buy a telescope as their first step in learning astronomy, when in fact that should be their last step. Many new telescopes end up in closets because their owners have no idea what to look at with their telescope or how to find it. Although it may seem old fashioned in this era of the internet and computers, I strongly recommend that any astronomical exploration begin with reading a book. NightWatch by Terence Dickinson (Firefly) to be very specific. This book is beautifully written and illustrated, and is the perfect introduction to astronomy for anyone of just about any age. Although written for adults, most children can grasp most of the ideas in the book wit a little bit of guidance from an adult. A second step in astronomical adventures is Starry Night software. There are many nice planetarium programs on the market, but none come with all the educational resources built in to every version of Starry Night. Starry Night lets you learn the sky under perfect conditions. No clouds, no light pollution, no bright moonlight. It shows you the sky for any place on Earth, any time of the year, any hour of the night. It lets you stop time, or run it fast forward or backward. It automatically labels anything you point at. If you see something that interests you, you can zoom in for a closer look. This has many advantages compared to the real night sky. No cold, no mosquitoes. Especially no mosquitoes! No complicated alignment procedures or balky mounts. No limitations on aperture and magnification. No dew or frost. Most planetarium programs offer all this. But Starry Night offers much more. In particular, the SkyGuide pane is the magic door into a wide realm of interactive tutorials, designed to cover all the basics of astronomy, plus many fascinating topics too advanced to be in most textbooks. Starry Night also has its Favorites menu. This provides links to a wide variety of simulations demonstrating many interesting things about the universe. I'm always finding something new under this menu. However, as endlessly fascinating as Starry Night may be, I still find myself out in the cold night with my binoculars and telescope. Yes, even with the mosquitoes. That's because, no matter how good or involving a simulation can be, there is still something magical about seeing the universe with your own eyes. The photons that reach your eye from, say, the Andromeda Galaxy, are unique to you. They have traveled for over two million years to arrive on your retina, and yours alone. And that is truly special! So, sooner or later, you will want to buy a telescope. What to buy and where? That's a story for another time. In the mean time, enjoy Starry Night! Geoff Gaherty

Clear nights are often few and far between, so I find that it helps to have specific observing targets in mind when I head out to a dark site with my telescope. If you are new to astronomy, let me recommend the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada's Explore the Universe Certificate program. This is a smorgasbord of observing targets: constellations, bright stars, the Moon, solar system objects, deep sky objects, and double stars. It doesn't require a telescope, only binoculars and naked eye. It also doesn't take forever, since there are many optional objects, so you can do it all in a few months. You don't even have to be a member of the RASC to participate. You can download the program checklist from the above web site. The traditional right of passage for telescopic observers is Charles Messier's list of wannabe comets. Messier was the first astronomer, back in the 18th century, to systematically search for comets. Along the way he was annoyed by objects which looked like comets, but didn't move. In order to make his comet hunting easier, he began to catalog these objects. His catalog of 110 objects became the first list of what we now call “deep sky objects.” These are objects which generally lie beyond the naked eye stars in the depths of space: star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies. Because Messier was the first to catalog them, his list is generally considered to be the best of the best. They are scattered widely through the sky, so that there are always quite a few visible on any given night. Start with the brightest objects, the open clusters, then go on to the fainter globular clusters, galactic and planetary nebulae, and finally to the far distant galaxies. So what do you do if you've now seen all of Messier's objects? There are a number of more advanced lists of fainter and fainter objects. One of the best is Alan Dyer's list of the Finest NGC Objects, published every year in the RASC's Observer's Handbook. Alan includes most of the showpiece objects that Messier missed, including many fine planetary nebulae. Suppose you've tired of “faint fuzzies” or live in a city where deep sky objects just aren't visible? Then try something different: double stars. Back in the early days of amateur astronomy, observers with small refractors tracked down hundreds of these astronomical jewels. Nowadays they often get overlooked, and that means that many observers are missing out on some of the finest objects in the sky. What's so exciting about double stars? Lots of things! First of all, they often come in strikingly contrasting colors, such as Albireo. Yet two equally bright stars the same color, like Castor, also have their attraction. Then there are the unequal pairs, like Rigel: a tiny speck of a white dwarf hiding in the blazing light of the primary star. There is an excellent list of double stars put out by the Astronomical League as their Double Star Club. The Astronomical League double stars aren't normally displayed in Starry Night, but you can download and install the list here. Each of these more advanced lists contains 100 to 110 objects, and will take most observers a year or two to complete. You may have heard of observers seeing all 110 Messier objects in a single night, but that's during an annual race known as the Messier Marathon for advanced visual observers. Most people take a more leisurely trip through these lists, and enjoy the many spectacular views along the way. Clear skies! Geoff Gaherty

Kuiper Belt Objects Beyond the Orbit of Neptune lies a constellation of large objects including four dwarf planets. Pedro Braganca

Don't let the scale of the diagram above fool you: Hydra is the largest constellation, and covers some 90° of sky. At this time of year, from mid-northern latitudes, it lies along the southern horizon at midnight. To start, M83 is an impressive barred spiral galaxy that, from our vantage point in space, lies almost face-on. Even small scopes should pick up its obvious structure. M68 is a nice globular cluster, 33,000 light years away. It's visible in binoculars but a telescope brings out the individual suns. NGC 3242, the Ghost of Jupiter, is one of the finest planetary nebulae in the sky. It's a full magnitude brighter than the more famous Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra. A small telescope reveals a pale blue disc with diffuse edges and the prominent 11th magnitude star. Due to its high surface brightness, this target takes high magnification quite well: try 200x or 250x to see the football-shaped interior and faint shell. NGC 3115, the Spindle Galaxy, is actually in Sextans. In contrast to M83, this galaxy is seen almost edge on. It's a lenticular galaxy, meaning it's a disc galaxy with very little spiral structure. Sean O'Dwyer

|

APR 2010

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||