|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For education orders please call 1-877-290-8256. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

From the dawn of recorded history our species has looked up at the sky and noted that of all the heavenly bodies, seven were different — they moved against the background of the stars. The Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn were found in the night skies and the Sun in the daytime sky. The Earth, of course, was the centre of creation and thus was not in the same category as stars and planets.

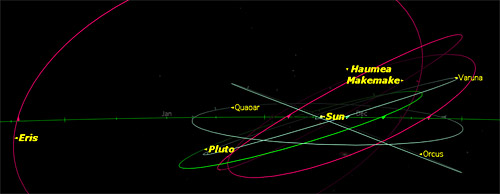

By the mid 16th century the special nature of the Sun was grudgingly recognized and it was promoted to the centre of the solar system. Earth was demoted from its exalted position and became just another planet. The Moon, which orbited the Earth, became the first of a new breed of object — a satellite orbiting a planet. The solar system had now dropped to six planets and one satellite. With the invention of the telescope and the passage of time more objects orbiting the Sun were discovered and, at one time, there were a total of 23 planets and numerous moons. But by the beginning of the 21st century this was whittled down to a more manageable nine planets and nobody really cared how many satellites. Pluto, the last planetary outpost, discovered in 1930, turned out to be a strange object. It was by far the smallest planet (smaller even than our Moon), its eccentric orbit at times brought it closer to the Sun than Neptune, and it strayed further from the ecliptic than any other planet. But, as it turned out, Pluto wasn’t the only “strange” object out there. During the last few years quite a number of objects with orbits as odd as Pluto’s have been discovered beyond Neptune. Pluto is now recognized, not as an oddball planet, but as the first of a new group of objects called dwarf planets. Any dwarf planet beyond the orbit of Neptune is now dubbed with the special term “plutoid”. At present, there are four plutoids: Eris (which is actually larger than Pluto), Makemake, Haumea and, of course, Pluto itself. They, along with thousands of similar bodies, inhabit a region of space called the Kuiper belt.

The Seven Planets of the Ancients The above illustration shows the four plutoids and several Kuiper Belt objects which might become plutoids if refined measurements show them to meet the IAU’s definition of a dwarf planet. With Starry Night, you can find the position of these KBOs at any time by using the following file: Make sure you have the latest update to Version 6 of Starry Night for all of these objects to show up. You might also be interested in a more complete version of Pluto’s change from planet to dwarf planet by reading my articles from past issues of Starry Night Times. They can be found using the following links:

Herb Koller

Last month I reviewed the Orion FunScope 76mm reflector which, at $49.95, is the least expensive serious telescope I’ve ever used. I was curious to see what you could get if you increased the price while still keeping it below the $199.95 price of the widely recommended Orion StarBlast 4.5. The GoScope 80mm ¡refractor reviewed here is one of the answers.

Orion has since released three larger telescopes on the same neat little mini-Dob mount. They have done this using a standard Vixen dovetail, so that all three optical tubes are interchangeable. In fact, you can mount any small telescope with a Vixen dovetail on this mount. The three new optical tubes are an 80mm refractor and a 100mm Newtonian reflector, both priced at $99.95, and a 90mm Maksutov-Cassegrain, which sells for $199.95. The mount, like the mounts for the FunScope and StarBlast, is excellent: smooth in motion and easy to use. It has a bonus of having a standard tripod socket on the base, so that it can be mounted on any standard camera tripod, if you don’t have a suitably solid table on which to sit it. The 80mm GoScope has a focal length of 350mm, yielding magnifications of 18x and 35x with the supplied 20mm and 10mm eyepieces. These magnifications may seem low to people used to department store telescopes which claim magnifications of 675x, but any experienced amateur astronomer knows that these are the magnifications used most often. The eyepiece holder accepts standard 1.25” eyepieces, so a wide variety of magnifications are possible. The Vixen-style dovetail has several holes to make a positive lock at various balance points, depending on the weight of the eyepieces you are using. The telescope focuses using a large rubber-covered knob which moves the objective up and down the tube. This is smooth and accurate. The red dot finder makes it easy to point the telescope at objects in the sky, or on land during the day. The 90° star diagonal attaches with a threaded ring, and becomes a permanent part of the telescope. This delivers images which are upright but reversed right to left. The focuser has a wide range, so that the scope can be used terrestrially as a long-distance microscope. Optically the scope is much better than the 76mm FunScope, delivering a sharp contrasty image. The major cloud belts of Jupiter were easily visible at 35x, as well as its four bright moons. There was a bit of chromatic aberration visible along the edge of the Moon, not surprising because of this scope’s very short focal ratio (f/4.4), but on the whole the view was very pleasing. Although I was only able to test the 80mm refractor, I’m sure that the Newtonian and Maksutov versions will be equally pleasant to use. The Newtonian offers a couple of major improvements over the FunScope: 4-inch aperture rather than 3-inch, and a parabolic figure on the mirror rather than spherical. The 90mm Maksutov is a tried and true design which has been popular for many years; the mini-Dob mount is an improvement over previous mounts offered with his scope. Geoff Gaherty

The doomsday predictions for 2012 are still around, much to the dismay of my colleague Geoff who wrote about the alleged galactic alignment last year, and they're just getting weirder. Here's another part of the 2012 hoax: 'Nibiru', a so-called rogue planet on a long elliptical orbit that will bring it into the inner solar system to collide with the Earth. This idea was proposed in the mid-1990s by people who believed they were telepathically communicating with aliens through brain implants — not exactly trustworthy experts. The timing of Nibiru's collision with Earth has been revised over and over again (originally 2003, then 2010, now 2012) and has been absorbed into the collection of random non-facts surrounding the Mayan calendar hoax, which it was not originally a part of! If an object this big was that close to Earth, it would be easily observable already.

Pictures of an eerie grey sphere with a red heart have been circulated with the claim that they are pictures of Nibiru, but these pictures are actually of V838 Mon, a star with a spherical expanding gas cloud. The speedy expansion of the cloud is easy to pass off as an object that is getting closer and appearing larger as it does so — if you aren't a Hubble Space Telescope fan who recognizes what it really is. Also, Nibiru is known to archaeologists as an ancient Babylonian word that is sometimes associated with the bright naked-eye planet Jupiter. I think there's a case of mistaken identity here. The 2012 doomsday scenario is based on an obscure interpretation of an ancient South American calendar system, the Long Count. The full timespan covered by this calendar is about 5,125 years long. This 'Great Cycle' started (if you convert to the modern Gregorian calendar) on August 13th, 3114 BC, which the ancient Mayans believed was the date of the creation of the world, and will end on December 21st, 2012 AD. The 31st Century BC was an important period in history. Writing was developing in Mesopotamia, great earth and stoneworks were being built in England, northern Africa was drying out and making times tough for herding and farming communities. South American people were just getting a foothold on their new continent, and some of the oldest known New World pottery comes from this time. Can you spot the problem? Yes, the world did in fact exist before 3114 BC. The Long Count is one calendar based on one culture's religion, and many religions have calendars that don't correspond with scientific analyses of the age of the world or civilization. If the beginning of the Long Count wasn't really the beginning, why should we think 2012 AD will be the end? Brenda Shaw

Winter Constellations Explore the winter constellations. Can you find Orion? Pedro Braganca

Perseus is the mythological hero who saved Andromeda from Cetus, the Sea Monster. Perseus used Medusa's head (lopped off in a previous adventure) to turn Cetus to stone. At this time of year Perseus is visible in the north-east after dusk. As the night progresses, it rises higher for excellent viewing, and there are a number of fabulous sights on show. NGC 869/884, the Double Cluster, is a favorite target and with good reason. Use binoculars to get an overview of this jewel box, then a low magnification in your telescope to bring out the distinctly varied coloration of stars in each cluster. Both clusters are about 7000 light-years away and are part of the Perseus arm, one of the spiral arms of our Milky Way. M76, the Dumbbell Nebula, is another favorite among observers because of its obvious hourglass/dumbbell shape. It's faint and small but responds well to magnification. Averted vision will help you see its two distinct lobes and nebulous wisps. NGC 1245, an open cluster, is best viewed with low magnification. Most of the stars are hot blue, but there are some nicely contrasting bright orange stars, cooler and older than their blue house mates. M34, another star cluster, contains about 60 members including several double-stars. The cluster is 1,500 light-years distant and is moving in the same direction through space as the Pleiades. NGC 1023, an very elongated looking galaxy, hangs in space roughly 30 million light-years from the back of your eye. From that distance it's surprisingly bright, especially the middle. Try all magnifications to pick out structure and details. NGC 1499, the California Nebula, is a large emission nebula. Under dark skies, it's bright enough to see with the naked eye. Use low magnification and a nebula filter if you have one. See if you can make out the shape of the state that gives the nebula its name. Sean O'Dwyer

|

JAN 2010

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||