For education orders please call 1-877-290-8256.

Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

If you go out every day at the same time, and measure the altitude and azimuth of the Sun, you will find after a year that the Sun has returned to the position it was in when you started your measurements. It will also have traced out a shape or a pattern, known as an analemma, in the sky.

Since you probably can't see the Sun every single day from where you live (e.g. because of weather), you can use Starry Night to make an analemma. You don't have to go outside, and it'll only take a few minutes rather than a year! Here's how:

- Find the Sun in Starry Night. You can open the Find tab and double-click on the Sun; or you can just scroll around the sky until you find it, and then right-click on it and choose Center. This should put the Sun in the middle of your screen.

- On the top menu bar click Options -> Orbit/Path Options... Tick the box for “infinite path length”. Click OK or close the options window.

- Right-click on the Sun and choose Local Path.

- Stop time by clicking the square stop button beside the clock in the upper left corner of the program.

- Click the day element of the date on the clock, so that it's highlighted.

- With the day element still highlighted, use the up arrow key or scroll your center mouse wheel forward to advance time in units of a single day at a time. You should end up with something that looks like this:

Why the heck does the Sun do this? To find out, you might want to ask yourself some questions about the shape of the analemma, and you can use the dates marked on Starry Night's analemma to help you figure it out.

- What parts of the year do the two “ends” of the figure-eight represent?

- What part of the year does the middle or crossover point represent?

- Does it matter what time of day you have Starry Night set to?

- Try changing Starry Night's location to somewhere else on the Earth. For example, if you live in mid-northern latitudes, move to a mid-southern location, or to a pole or somewhere on the equator. What do these different positions do to the analemma?

- Does the appearance of the analemma from different locations on Earth give you a clue as to why the Sun makes this pattern?

Tune in next month to check out the answers.

Brenda M. Shaw is not a very good skater and might ask the Sun for some coaching on that figure-eight thing.

[Top of Page]

Last time, we learned that the Sun reached its maximum northern declination around June 21 ushering in summer in the northern hemisphere. The northern latitude where the Sun is directly overhead at noon defines a great circle at about 23.5 º N known as the Tropic of Cancer.

But why “Cancer” when the Sun is actually in the constellation Taurus?

Summer Solstice 2010 AD

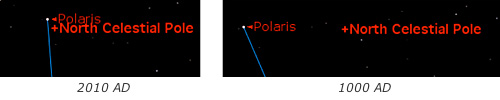

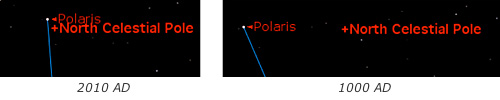

Because of the Earth’s axial tilt, gravitational forces exerted by the Sun and Moon cause its axis to wobble like a spinning top. As a result, the North Celestial Pole and the Celestial Equator move in relation to the stars in a process called precession. Because of the Earth’s axial tilt, gravitational forces exerted by the Sun and Moon cause its axis to wobble like a spinning top. As a result, the North Celestial Pole and the Celestial Equator move in relation to the stars in a process called precession.

This in turn, causes points like the equinoxes and the solstices to move westward along the ecliptic at the rate of about one constellation per two thousand years. This is only approximate since not all constellations are of equal width along the ecliptic and one precession cycle takes about 26,000 years.

So the Sun was indeed in the constellation Cancer when relevant observations about the summer solstice were made about two thousand years ago.

Another effect of precession is that Polaris, our current north star will not retain its title as time progresses. In 2010, Polaris is less than one degree from the North Celestial Pole but the separation was over 6 degrees about a thousand years ago.

To see how the North Celestial Pole wanders among the stars use Starry Night to run the file Precession.snf.

Further Study

This month there are two questions regarding precession. We now know that the Sun is currently not in the constellation Capricorn at the winter solstice and Polaris is not always our North Star.

- In what constellation do we find the Sun during the upcoming winter solstice?

- What was the North Star when the pyramids were being built?

Check the next Starry Night Times for the answer.

Answer to last month’s question: At the summer solstice, the Sun has an altitude of 90º at the Tropic of Cancer (latitude 23.5º) and drops by 1º in altitude for every degree of latitude as we head north. Latitude 66.5º represents the lowest northern latitude at which the Sun does not set on summer solstice day. It is also known as the Arctic Circle.

Herb Koeller

[Top of Page]

Judging by the number of questions I see on Yahoo! Answers about this, it must be a popular exercise for teachers to assign their students. Properly implemented, it can teach students a great deal about the motions of the Moon and also the challenges of astronomical observation and research.

The idea is to observe and record the appearance and position of the Moon over a complete lunar cycle. This sounds simple, but students can find it a challenging exercise.

I have a suspicion that quite a few teachers assign the exercise without ever having tried it themselves, and are unaware of the difficulties which even a student with the best intentions may run into. So I urge teachers to try the exercise with your students.

Right at the outset, it seems that quite a few students will forget they have to do this project and, a month later, they will be on the internet frantically looking for pictures of the Moon for every night. So it’s important to remind them at some point every day, preferably at the end of the school day.

Usually things go smoothly for the first two weeks of the lunar cycle, from New Moon to Full Moon. Inevitably there will be problems with weather, and its important to warn kids ahead of time that as scientists they need to record negative observations as well as positive ones. So they should record every time they looked at the sky, including the date, time, and weather conditions. Once a night is not often enough, as they will often look when the Moon is simply not in the sky. It’s important to look in the late afternoon, early evening, just before bedtime, and first thing in the morning.

Many students have the mistaken belief that the Moon is visible only at night, so it’s vitally important that they also check the daytime sky. This becomes crucial in the two weeks after Full Moon, because the Moon rises almost an hour later every night, which soon puts it well past most students' bedtimes.

Where's Luna?

Often the best time to spot the Moon in the second half of the lunar month is around 8 a.m.

I would also urge the students, once they’ve located the Moon, to check on its position every hour or so, if that is practical. This will show them how the Moon moves across the sky, day or night. It’s especially important that they observe moonset (just after New Moon) and moonrise (around Full Moon); it’s amazing how many adults have never learned that the Moon, like the Sun, rises and sets every day/night.

A very large number of students “lose” the Moon right after Full Moon. They need to be reminded that the Moon is visible for close to 12 hours every single day, but those 12 hours are not always the same. Many of those hours are in daylight. This is a good place to use Starry Night to figure out exactly when the Moon rises and sets on a given day, using the Info pane.

When I see a student on Yahoo! Answers in panic mode over this assignment, I often suggest that they approach their teacher and request a second month to complete the project. Since learning about the Moon’s movements is more important than grading, I urge you to be open to such requests. This really is quite a difficult assignment because it requires children to be up checking the skies at times way outside their normal bedtimes. Some preparation of their parents for these tasks is also advisable.

Geoff Gaherty

Geoff has been a life-long telescope addict, and is active in many areas of visual observation; he is a moderator of the Yahoo "Talking Telescopes" group.

[Top of Page]

Give your kids an advantage! When you refer their teacher to our educational solutions, the school will receive 10% off their purchase and you'll receive 15% off your next selection at the Starry Night Store!

Here's how it works:

- Tell your school's science teacher or curriculum decision maker about Starry Night Education or The Layered Earth;

- Give them coupon code "Back to School 2010!" for their next curriculum purchase;

- Let us know that you've done so by submitting the school, grade, subject and teacher's name, here;

- We'll send your discount code to you, immediately;

- Pick out your next, great Starry Night product!

Let us know if you've any questions, and thanks again

[Top of Page]

Solar System Boundaries

Press the Decrease Elevation button to fly through various solar system boundary layers. To identify the various boundary layers by color, click on the contextual menu button of the Sun in the Find pane and select Distance Spheres.

Pedro Braganca

Education & Content Director

Starry Night® Education

[Top of Page]

NGC 6960 & NGC 6992, the West and East Veil Nebulas, are part of the Cygnus loop, the remains of a supernova that exploded over 100,000 years ago. Two other sections, NGC 6995 and 6979 are close by.

M29 is an unimpressive open cluster, notable only in that it was one of the original discoveries of Charles Messier.

NGC 6819 is a small open cluster with about two dozen stars from 10th to 12th magnitude within a 5' circle. Its discovery in 1784 is attributed to Caroline Herschel.

Deneb, which marks the tail of the swan, is one of the 20 brightest stars in the night sky. Just three degrees away lies NGC 7000, the North American Nebula, so-called because of its obvious shape. This is an active star forming region and quite large, though it's difficult to see without the aid of astrophotography.

M39 is an open cluster, and is a nice binocular object with 30 or so stars spread over its seven lightyear diameter. It's also "pretty close" to Earth, at "just" 800 lightyears.

Finally, NCG 6826, the Blinking Nebula, gets its name from an odd phenomenon: its central star appears to blink on and off when you look toward and away from it quickly.

Sean O'Dwyer

Starry Night® Times Editor

[Top of Page]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Navigating A Lesson In The Layered Earth

Take a sneak peak at The Layered Earth in this video, a new Geology curriculum from the makers of Starry Night.

|

|

|

Pedro Braganca

Education & Content Director

Starry Night® Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below the Horizon

Objects in the Find pane that are below the horizon will be greyed out. You can still click on the object and Starry Night will give you the option to view the object when its above the horizon.

Pedro Braganca

Education & Content Director

Starry Night® Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow us at

• twitter.com/starrynightedu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moon Phases

Wed., September 1 Wed., September 1

Last Quarter Moon, 1:22 p.m.

The Last or Third Quarter Moon rises around 11 p.m. and sets around 3 p.m. It is most easily seen just after sunrise in the southern sky.

Wed., September 8 Wed., September 8

New Moon, 6:30 a.m.

The Moon is not visible on the date of New Moon because it is too close to the Sun, but can be seen low in the east as a narrow crescent the morning before, just before sunrise.

Wed., September 15 Wed., September 15

First Quarter Moon, 1:50 a.m.

The First Quarter Moon rises around 3 p.m., and sets around 11 p.m.

Thu., September 23 Thu., September 23

Full Moon, 5:17 a.m.

The Full Moon which falls closest to the autumnal equinox is known as the Harvest Moon. Other names are Corn Moon and Barley Moon. In Hindi it is known as Bhadrapad Poornima. Its Sinhala (Buddhist) name is Binara Poya. The Full Moon rises around sunset and sets around sunrise, the only night in the month when the Moon is in the sky all night long. The rest of the month, the Moon spends at least some time in the daytime sky.

Observing Highlights

Sun., September 19, pre-dawn

Mercury greatest elongation west

This is the best morning of the year for observers in the Northern Hemisphere to see the elusive planet Mercury as a “morning star.”

Wed., September 22, evening

Jupiter, Uranus, and the Moon

Just after sunset, if you look to the east you will see the Full Moon rising. Soon it will be joined by brilliant Jupiter, just below it, one day past opposition with the Sun. Look closely with binoculars or a small telescope, and you will see the tiny planet Uranus, also just past opposition, a degree above Jupiter and its moons.

Thu., September 23, evening twilight

Venus at greatest brilliancy

As Venus draws closer to the Earth, it looms larger in size, but its crescent grows narrower in as it moves in front of the Sun. Tonight it reaches its greatest illuminated extent, and hence is at its most brilliant, magnitude 4.8.

Planets

Mercury will be a “morning star” in the second half of the month, reaching greatest western elongation on the 19th. This apparition is better for observers in the Northern Hemisphere.

Venus is still a brilliant “evening star” visible in the west after sunset. Because of the low angle the ecliptic makes with the horizon at this time of year, Venus will be low in the southwest. Venus spends most of September in Virgo, passing into Libra on September 24. In a small telescope, Venus becomes a narrower but larger crescent. It will be at its brightest on September 23.

Mars is vanishing into twilight in the western sky after sunset. Like Venus, it spends most of September in Virgo and moves into Libra on September 26.

Jupiter is in opposition to the Sun on September 21. It rises around sunset and is visible the rest of the night, dominating the southern sky. It is in the constellation Pisces all month.

Saturn begins its passage behind the Sun. When it emerges in the dawn sky in late October its rings will begin to be restored to their usual glory.

Uranus is in opposition on September 21 also, just five hours after Jupiter. The two planets are in conjunction the next night, less than a degree apart.

Neptune is visible most of the night on the border between Capricornus and Aquarius.

Geoff Gaherty

Data for this calendar have been derived from a number of sources including the Observer's Handbook 2010 of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Starry Night® software, and others. Only events with a reasonable possibility for Northern Hemisphere observers, or those events with some other significance, are given. All times shown are U.S. Eastern Time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prepare Your Students for NCLB Science Testing

Starry Night® gives you and your students engaging stimulations and easy-to-follow lesson plans that teach the critical space science concepts in the NCLB science assessments.

Written by teachers, for teachers, each unit includes interactive and hands-on activities that will spark your students' curiosity.

Click here to download full brochure.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education Minnesota Professional Conference

October 21-22, 2010: Saint Paul, MN

NSTA Area Conference

October 28-30, 2010: Kansas City, MS

Science Teachers' Association of New York State (STANYS) Conference

November 6-9, 2010: Rochester, NY

CAST (Science Teachers' Association of Texas) Conference

November 10-13, 2010: Houston, TX

Science Teachers' Association of Ontario (STAO) Conference

November 11-13, 2010: Toronto, ON

NSTA Area Conference

November 11-13, 2010: Baltimore, MD

NSTA Area Conference

December 2-4, 2010: Nashville, TN

Details...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Educational Inquiries and Sales

Please contact Michael Goodman for all education inquiries. EDUCATION ORDERS 1-877-290-8256

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Send us your feedback

Do you have a question, comment, suggestion or article idea to pass along to Starry Night® Times?

Click here to get in touch with us.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Starry Night® is the world's leading line of educational astronomy software and DVDs. Visit store.starrynight.com to see all the great products we offer for everyone from novice to experienced astronomers.

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download or as a registrant at starrynight.com.

To subscribe sign up here.

Starry Night® is a division of Simulation Curriculum Corp.

Simulation Curriculum Corp.

Starry Night® Education

11900 Wayzata Blvd.

Suite 126

Minnetonka, MN 55305

Tel:

1-866-688-4175

|

|

|

|

Because of the Earth’s axial tilt, gravitational forces exerted by the Sun and Moon cause its axis to wobble like a spinning top. As a result, the North Celestial Pole and the Celestial Equator move in relation to the stars in a process called precession.

Because of the Earth’s axial tilt, gravitational forces exerted by the Sun and Moon cause its axis to wobble like a spinning top. As a result, the North Celestial Pole and the Celestial Equator move in relation to the stars in a process called precession.