|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For education orders please call 1-877-290-8256. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial and earth science events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

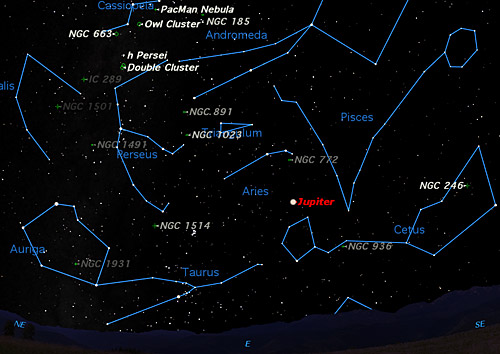

Beginning amateur astronomers are often puzzled about what they should look at with their new telescopes. They've "seen" the Moon, a planet or two, but what is next? There are lots of stars up there, but they all look pretty much the same. There are supposed to be “deep sky objects” but how to find them? Starry Night to the rescue! Starry Night offers a wide variety of catalogs of observing targets, enough to keep most astronomers busy for the rest of their lives. These catalogs can be displayed by turning them on under "Options" and then labeled by turning on their labels under the Labels menu. But, with such an assortment, where to start? Messier’s Catalog Probably the most popular list of observing targets for the beginning astronomer is the catalog put together in the 18th century by comet observer Charles Messier. In his search for comets, Messier started keeping a list of comet look-alikes to make his identifications easier. He had little idea what these objects really were; his main concern was that they looked a lot like distant comets. The idea of getting beginners observing Messier’s catalog originated with Canadian amateur astronomer Isabel K. Williamson. In the early 1940s she despaired of all the amateur astronomers with lovely telescopes who never ever used them. She wanted to encourage observing, so she started a “Messier Club”: a friendly competition to see how many Messiers people could observe. When I joined the RASC’s Montreal Centre in 1957, Isabel’s Messier Club was one of the most popular activities, and I soon got caught up in it. Two years later I was the fourth person to “graduate” from the Messier Club, making me one of the first people in the world to have seen all of Messier’s objects. Nowadays, people compete in Messier Marathons to observe all the Messier’s in one night, but things were much more leisurely back in the 1950s! What is the appeal of observing Messiers? First of all, they are the brightest and best of all the deep sky objects. Although Messier missed a few gems, such as the Double Cluster in Perseus, he got most of the finest objects in the sky. The objects are spread around the entire sky, making it possible to start at any point in the year. Finally, a list of 110 objects is a manageable target. Although these are the easiest objects in the sky, there are plenty of challenges. Some are located in obscure areas in the sky with few bright stars to starhop from. Others are just plain difficult for a beginner, unused to looking at faint objects, to see, even if they’re looking right at them. Observing the Messiers develops two important skills. First is learning to find faint objects. Because of this, I recommend turning off your telescopes GoTo feature and learning to find the Messiers the old fashioned way, by star hopping. Second is learning how to see faint diffuse objects. This requires special skills and tricks such as averted vision (looking slightly to one side of the object to put it on the more sensitive area of the eye) and tapping the telescope to make the object move slightly (since we can see moving objects more easily than stationary ones). The Messiers include almost all the major types of deep sky objects, the only exception being dark nebulae. There are star clusters, both the open scattered variety and the condensed and rich globulars, nebulae of many kinds, and galaxies. And more galaxies. Nearly half the objects in Messier’s catalog are galaxies, a whopping 40 out of 110. Here are the Messier objects visible looking eastward on an early October evening:

These include a number of galaxies on the right, including two of the nearest and brightest, Andromeda and Triangulum, a number of open clusters on the left, including the Pleiades, a supernova remnant, the Crab Nebula, and a planetary nebula, the Little Dumbbell. Notice how Starry Night shades the labels to give an indication of how easy or difficult the objects are to see. The Pleiades and the Andromeda Galaxy are easy, the Little Dumbbell planetary nebula quite difficult. Beyond Messier When Isabel Williamson was asked what to do after finishing the Messiers, she replied “There are always the Herschels.” Sir William Herschel catalogued about 2600 deep sky objects. Isabel intended it as a joke, but there are at least two people, both Canadians, who have observed all 2600 of Herschel’s objects. But for most of us this is a daunting task, and so there a number of shorter, more doable lists. Probably the best of these lists is the Finest NGC Objects compiled by Alan Dyer and published each year in the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Observer’s Handbook. This is also available online <http://messier.seds.org/xtra/similar/rasc-ngc.html> and included as one of the Deep Space options in Starry Night. This includes “the best of the rest” of the deep sky objects, another 110 objects. Here is the same view of the October sky showing the Finest NGC objects:

Again there are galaxies to the right and open clusters to the left, including the double Cluster in Perseus, and the Owl Cluster in Cassiopeia, a perennial favorite at fall star parties. There are also several emission nebulae and planetary nebulae; Messier missed many of these because of the small instruments he was using. At low magnifications small bright planetary nebulae are easily mistaken for stars. Another longer list is the Herschel 400, put together by Lucian Kemble for the Astronomical League. The Astronomical League also has a second list of a further 400 objects. (One list I suggest you avoid is the Caldwell list. This was put together by Patrick Moore, who has little experience in deep sky observing, and his list includes many poor choices for a visual observer.) Many of these lists are already installed in Starry Night, depending on which version you have, but may need to be turned on. If your version of Starry night is lacking a particular database, do not despair, as they are all available online. Geoff Gaherty

No, it's not a spelling mistake. Nebula is the Latin name for cloud and the plural in Latin is nebulae. These objects got their name due to their cloud-like appearance in telescopes and some have been recognized without optical help. Perhaps the most famous example is the Great Nebula in Andromeda. It was first observed as a hazy patch by a Persian astronomer over one thousand years ago.

This nebula was number 31 in the 18th century astronomer Charles Messier's list of objects and is now best known as M31. But surprisingly the Great Nebula in Andromeda is not a nebula at all. In the 19th century the newly invented spectroscope showed its spectrum to be that of stars. We now know M31 to be a galaxy composed of as many as a trillion stars stretching over 140 thousand light years at a mind-boggling distance of 2.5 million light years from Earth. In contrast to the neat spiral structure of M31, the Great Nebula in Orion has a diffuse form. Messier catalogued it as number 42 in his list. Its spectrum resembled that of a gas under low pressure.

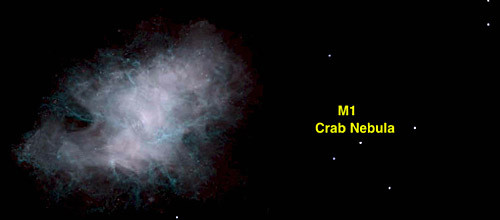

Here indeed was a true "cloud" in space. At a distance of about 1300 light years, it is part of our Milky Way galaxy. It is also much smaller than M31 spanning "only" about 25 light years. Another nebula in the Milky Way galaxy is M8, the Lagoon Nebula in the constellation Sagittarius. This interstellar dust and gas cloud is about 4100 light years from Earth and spans 55 light years at its widest. Like M42, its color is reddish and there seem to be groups of stars embedded in the nebula. Is this common to all nebulae? And what makes them glow in the first place? Let's look at another example of a nebula, M1, the Crab Nebula, in Taurus. With a diameter of about 5 light years, it is the smallest of the three nebulae we examined. But that's not all that's different about this nebula.

No overall red color and no apparent embedded stars! Clearly this nebula is different from the other two. But why? And what about B 133? It is clearly not seen in the image below That's right, it is an example of a dark nebula!

What makes this nebula dark? We seem to have a lot of questions but no answers. But do not worry! We shall endeavor to answer these and other questions regarding nebulae in the coming months. In the November issue of Educator's Corner we shall investigate M42 in more depth, so stay tuned! Further Study You can find the nebulae discussed this month in any version of Starry Night. Use Starry Night's Find tab to locate the nebula designated as IC 434.

Answer to last month's questions:

Herb Koller

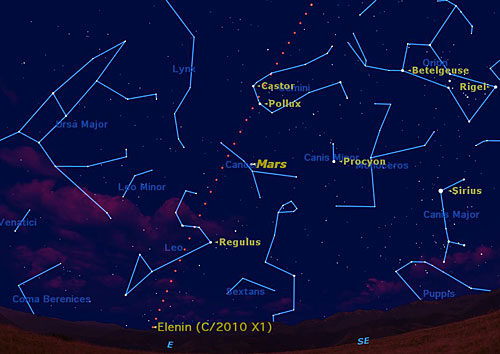

Discovered last December by Russian amateur astronomer Leonid Elenin, Comet C/2010 X1 was a rather small and ordinary comet which promised to put on a bit of a show this week. It had the misfortune to become a media darling. Partly this was because of a strange interpretation put on its name. Some interpreted it as an acronym: Extinction Level Event—Nibiru Is Nigh. Others claimed it was a brown dwarf or the errant planet Nibiru. It was going to hit the Earth. It was going to block the Sun’s light for three days. It was a spaceship steered by extraterrestrials. In early August, it was shaping up nicely, and was being photographed every night by amateur astronomers in Australia. Then, on August 19, disaster struck in the form of a coronal mass ejection from the Sun which literally blew Elenin to pieces. In a matter of hours its brightness dimmed from 8th magnitude to less than 11th magnitude. Then on September 10 it passed perihelion, and what little of it was left was melted. It should have been visible on SOHO’s cameras from September 23 to September 29, but there was no sign of it. For images of Elenin’s last days, go to: Here is Starry Night’s map of what would have been its path through the pre-dawn sky this month:

R.I.P. Elenin. That’s what happens when fame goes to your head. Or is it your tail? Geoff Gaherty

Total Solar Eclipse in 2017 Looking forward in time at the 2017 Total Solar eclipse that will be visible in North America. Pedro Braganca

At this time of the year, as seen from mid-northern latitudes, Aquarius glides low above the southern horizon, between Capricorn to its West and Cetus to its East. The Saturn Nebula (NGC 7009) is an oval Mag 8 fuzzy patch hanging in space about 4,000 lightyears distant. Medium-sized scopes show a ring with "knobs" on either side. M72, close by, is a small remote globular cluster, difficult to resolve. The open cluster M73 is a tiny triangular collection of stars, barely noticeable. However, the same field of view contains a lovely Lyra-like asterism. The Mag 7 globular cluster M2 is about 40,000 lightyears away. Although among the brightest of globs in the sky, M2's core is so concentrated that, as an observational object, it ranks as one of the less compelling. The Helix Nebula (C63/NGC 7293) is a tricky target. Although it is the largest visible planetary in the night sky (about half the apparent diameter of the full moon) it's quite dim. Dark skies are a must. A low-power eyepiece in your telescope, with averted vision, may give you some hint of structure. Finally, at 103 lightyears distant is one of the sky's finest doubles, Zeta Aquarius. Sean O'Dwyer

|

OCT 2011

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EDUCATION ORDERS 1-877-290-8256

EDUCATION ORDERS 1-877-290-8256